Over the past century there have been many innovative ways used to ‘shine a light’ on watch dials — right from backlit LCD screens to mini light bulbs built into the case. We explore the journey of luminescence in watchmaking over the past few decades

Whether you’re a diver, deep under the surface of the water or deep asleep surfacing from the arms of Morpheus, there are times when there is a need to check the time in low-light conditions. In some cases, it’s a matter of life or death, such was the case in the 1950s with the advent of recreational diving when your dive watch was the most important piece of safety equipment on your list. Over the past century there have been many different innovative ways to shine a light on the time, from backlit LCD screens to mini light bulbs built into the case. The tried and tested method of painting or filling the hands and hour plots with luminous material has always been the favorite. It hasn’t, however, always been the safest…

Risky Radium

The story of the discovery of radium is a fascinating one. The element was discovered by husband and wife team Pierre and Marie Curie in 1898. They were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1903 and following the tragic death of Pierre in 1906, Marie went on to win it for a second time in 1911. She was responsible for developing mobile x-ray units for in-field use in World War One, as her work on radiation was key in the development of accurate x-ray technology. She became a leading light in the research of cancer treatment and today, one of the most significant cancer charities in the UK, is named after her.

In its infancy, it was believed that radium had healing properties and so was used in drinks, toothpaste and even hair creams! From around 1915, radium also was the go-to substance for situations when luminescence was desirable on objects such as clocks, watches and military instruments. The Radium Luminous Material Company was founded in the USA in 1914 and began supplying radium-laced luminous paint to watch companies. It was typically ladies who worked in dial manufacturing facilities, especially in the United States, and they were responsible for painting dials and hands of watches and instruments. Now known as the Radium Girls, a great number of them died as a result of being exposed to the radioactive paint. The girls were told to ‘point’ their paint brushes using their lips, instead of clothes to avoid unnecessary wastage. They developed terrible tumors on their faces and mouths over time.

Warning Signs

By the early 1960s, the world began to recognize that radium was unsafe. The watch industry was one of the leading sectors in the use of radium and had to quickly adapt its practices to make watches safe. To be clear, the biggest risk wasn’t to the wearer of the watch. The case back and watch crystal offered a decent level of protection from the radiation. The most at risk were the watchmakers who disassembled the watches and worked on them. History tells us in the early 1900s Marie and Pierre Curie both suffered from radiation sickness, but it took a long time for scientists to truly understand the deadly nature of it.

One of the most famous and earliest moments of radium recalls in the watchmaking world was when Rolex asked for the original bakelite bezels on the reference 6542 GMT-Master to be taken back to Rolex Service Centres to be replaced with safe aluminium versions. The bakelite bezels were filled with radium to make the bezels readable in low light. Even now, these bezels emit high levels of radiation when tested with a Geiger counter. The watchmaking world widely adopted tritium as its new luminous material of choice, but the transition from radium was a tricky one to manage.

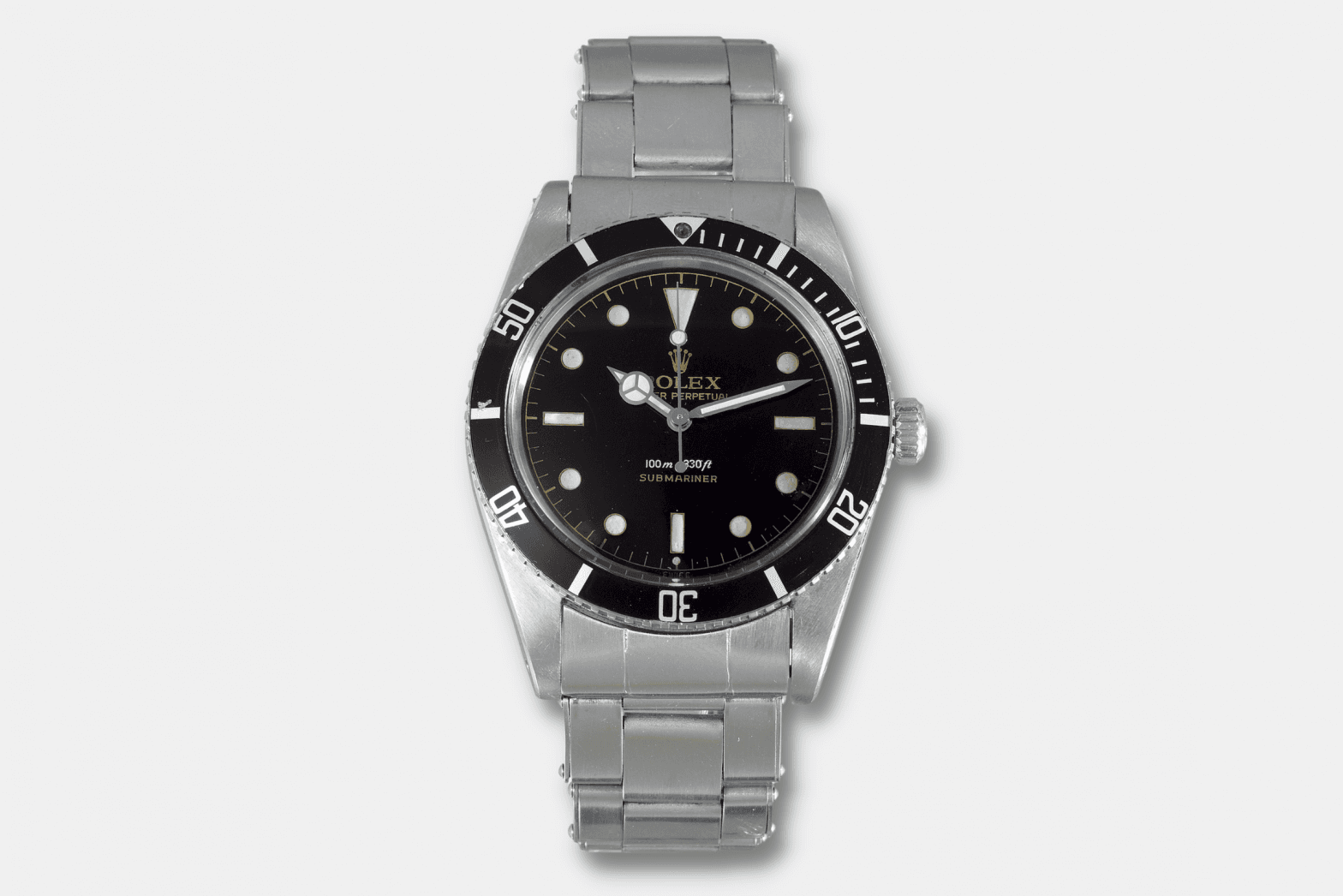

In the early 1960s, Rolex began significantly reducing the amount of radium in the luminous material used to paint the hour plots on its sports watches. Submariners, Explorers and GMT-Masters needed bold hours and so were heavily radioactive. Both Rolex and Tudor began adding a small dot under the six o’clock marker on their dials in 1962. This was a signal for watchmakers and those handling the dials at manufacturing that the dials were safe. These dials are now known as these exclamation dot dials, as the dot of luminous positioned below the narrow rectangular six o’clock marker resembles an exclamation mark! The Wilsdorf brands also used a small underline to denote safer levels of radiation. The little dash or line could appear in either the lower or upper half of the dial beneath the text, hence the term underline.

Safer Havens

The move to tritium was absolute once radium was outlawed in 1968. Tritium, whilst still radioactive, is far safer than radium and was in use in watchmaking up until the late 1990s. Due to its radioactive nature, watch brands still had to signal that tritium was present on the dials. Rolex and Tudor used markings such as “T SWISST” and “SWISS T <25”, the latter of which indicated that tritium was present but at less than 25 mCi. The last use of Tritium by Rolex was signified by “T SWISS MADE T” that meant the tritium was less than 7 mCi. Going back to the beginning of this piece, mCi is a measurement of radiation known as milliCuries after Marie Curie.

The scientific term for tritium is hydrogen-3, with tritium coming from the Greek tritos for third. 3H was used on dials by the German military for watches with tritium hour markers. The well-known Heuer Bundeswehr Chronographs that were issued to military personnel had to have a red 3H in a circle, as stipulated by the government. However, by 1998 Tritium was also outlawed for use on watches and a new phosphorescent substance became the industry standard: SuperLuminova® .

Kenzo Menoto had been in the luminous paint business since World War Two and as early as the mid-1940s was experimenting with novel ways of creating non-radioactive materials for his work. He founded Nemoto & Co in 1962 and after three decades of trial and error he launched his new brand name LumiNova that later became SuperLuminova®. Luminova was his branding of the substance strontium aluminate, phosphorescent pigments that could be charged with light, a bit like a battery, and then emit a glow for prolonged periods of time. SuperLuminova® is still the most widely used lume substance in the watchmaking industry, with the very latest iteration being Grade X1 that has recently been used on the Tudor Pelagos FXD. Of course, Rolex always beats its own path and in 2008 unveiled its proprietary substance called Chromalight.