It's the part of a watch you end up staring at the most, but have you ever wondered what goes into a watch dial?

Nine times out of ten, the first thing you will fall in love with on a watch is the dial. Perhaps it's the vivid colour, the fine details or the texture, or perhaps it's just the clarity of the design. There's a reason why dial condition is so important, and why — in vintage watches at least — a well-preserved (or well-patina-d) dial can make or break the value of a watch. Regardless of how simple the dial itself might seem to be, constructing it is anything but. Take, for example, a pretty common type of dial—a time-only watch, with applied logo and markers. In addition to all the steps it takes to finish and treat the dial, there's dozens of parts that go into the dial itself. Each hour marker is a separate piece that needs to be secured with numerous tiny pins. Typically, we think of the watch calibre as the most complicated part of a watch. However, while dials lack the moving parts, they're still complex, artisanal creations that play a critical role, so it’s important to give it the respect it deserves.

A blank slate

Before we dig too deep into the details of apertures, applied indices and guilloché, let's talk about the fundamentals. What is a dial made of? The vast majority of watch dials consist, at the base level, of a simple disc of metal. Brass is common, and so is gold. But other materials like steel and titanium are also used. The important thing about this sort of dial blank, as they're called, is that it's strong enough to handle everything that goes into turning this simple, small disc into a fully formed dial.

This basic dial blank can be pressed to give it a pattern, apertures might be punched out or different finishes applied; to create a sunray effect or a fine brushed look, for example. Holes will be drilled for the hands. Galvanic treatments might be applied to give colours or coatings. If a dial is a lacquer dial, the base metal dial has been coated with enamel paint known as lacquer and then fired at temperature to achieve a glossy look.

Even though lacquer involves enamel paint, don't mistake it with a vitreous enamel dial — commonly called Grand Feu enamel. This technique starts off with the thin metal disc, but rapidly gets more complex. Finely ground enamel is applied to the blank, and fired in a kiln at 800 degrees Celsius. After firing, the dial is checked, finished and re-fired to give the correct colour and appearance. Grand Feu enamel dials are finely crafted one-offs, and because of the skill required and high margins for error, the process of making them cannot be industrialised.

More challenging than enamel dials are dials made from semi-precious stones and uncommon materials like meteorite. Thin slices of fragile stones such as lapis lazuli or malachite are painstakingly cut and worked to show off their natural structure, and require immense care because a single crack or flaw renders the entire dial useless.

Bare bones

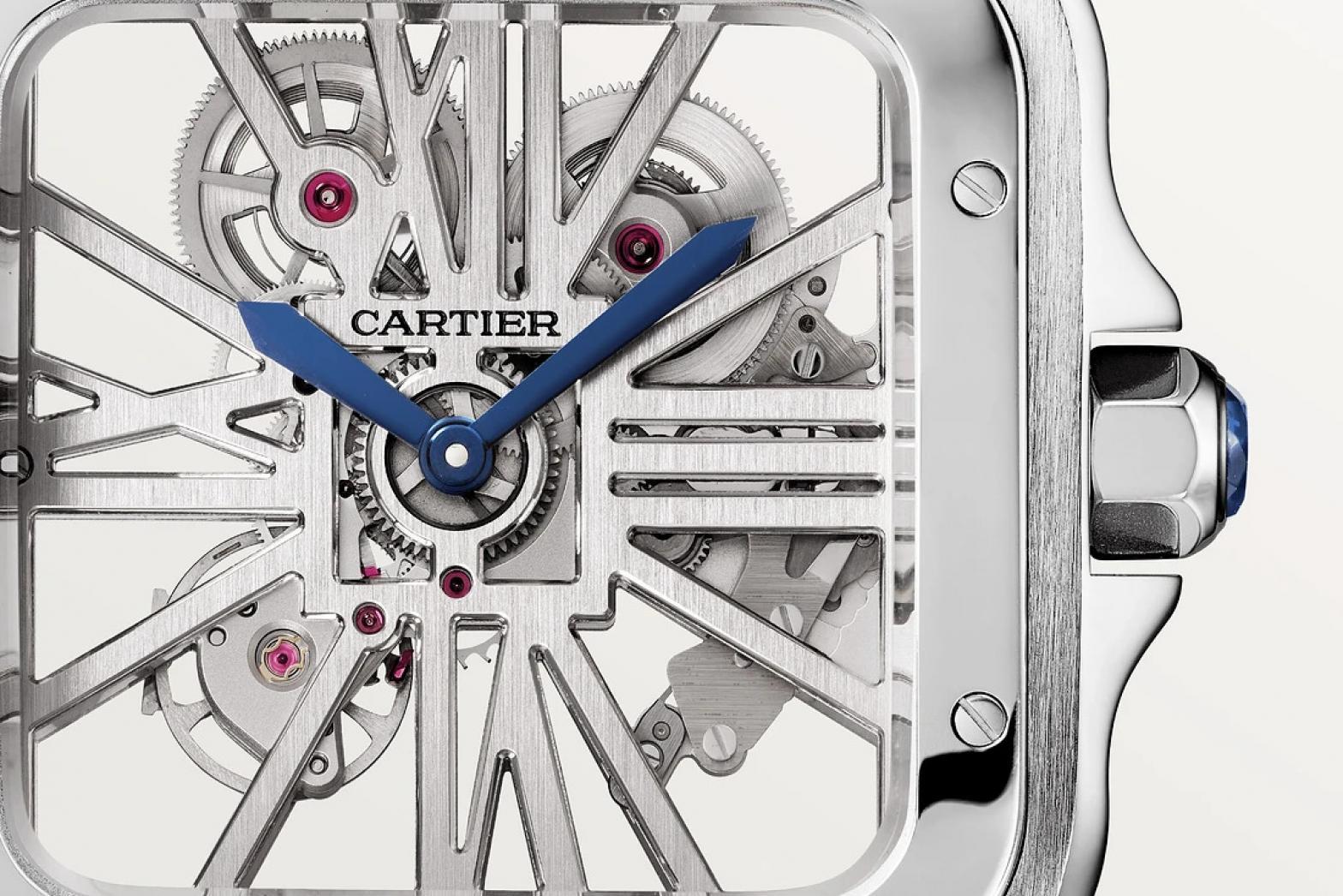

Not all dials cover up the movement. Some want to show it all off. One way of doing this is with a sapphire dial, popular with brands like Richard Mille and Hublot, and is complex in that an exceptionally thin piece of sapphire is a delicate material to work with. Another way of achieving the same effect is with a skeleton — or open-worked — dial. This technique sometimes sees the design of the calibre serve as the dial; take for example Cartier's famous open-worked designs, where the bridges of the movement are formed like Roman numerals.

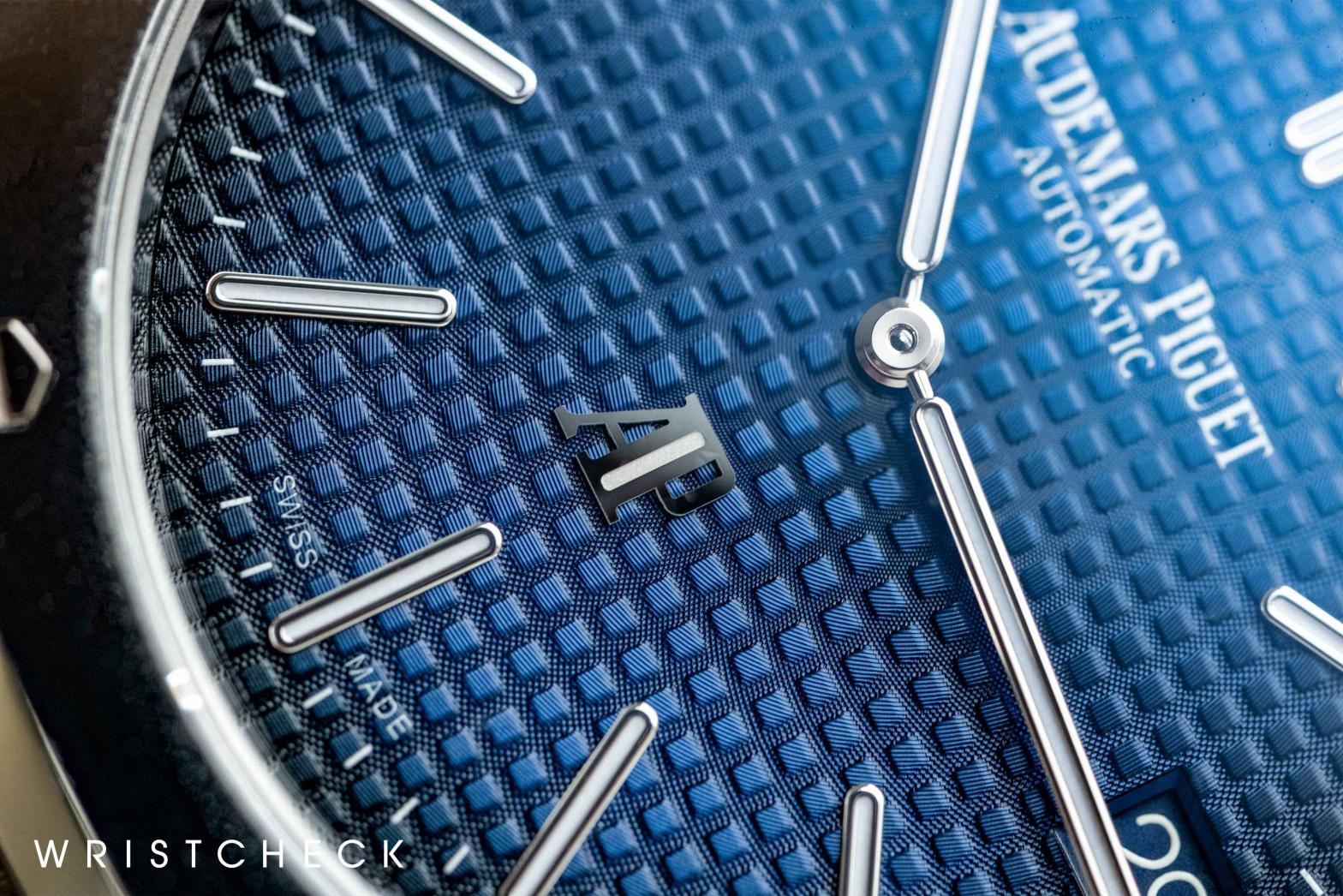

It's worth noting that a skeletonised dial is something different; rather than being designed from the ground up to be open, a skeletonised watch is one where elements of a regular dial have been 'cut-away' to reveal the mechanism below. Audemars Piguet is one of the brands that is constantly praised for having high quality openworking in their watches. It’s a technique that the brand has been using for decades where they cut the plates and bridges with precision before decorating and finishing them by hand.

The final touches

These are some of the ways a dial is made. But it's how a dial is finished that separates the good from the great. Many dials will have an element of printing, using a technique known as pad printing, where ink is applied to a large soft balloon-like pad, which is then softly pressed onto the dial, ensuring a clean and accurate transfer of ink. Sometimes the details like hours, logo and the like are made separately and applied by hand, a painstaking process that adds richness and depth. But processes like guilloché take it to the next level.

Guilloché, or guillochage, is engraving a repetitive pattern on the dial using a hand-driven machine. Breguet is particularly well-known for its diverse and beautiful guilloché, but arguably the most famous example is the 'clous-de-Paris' pattern used by Audemars Piguet on the Royal Oak, i.e. the Tapisserie.

Giving function to the form

So far, we've discussed the structure and aesthetics of a dial, but not the actual functional purpose they serve. Hours and minutes are pretty self-explanatory, as is a date window. Even more esoteric complications like day and month are pretty self-explanatory. Things like power reserve, which indicates how much running time your mechanical watch has left, are undeniably useful, while something like a moon phase is charming, but pretty niche. Where things start getting interesting is chronographs. Not the functionality of the chronography itself, which is typically displayed in a series of registers or sub-dials with one for each unit of time (typically hours and minutes, with the central chronograph hand measuring elapsed seconds), but things really start getting busy with the chronograph scales. Typically laid out around the outside of a dial, these allow the wearer to accurately determine a very specific piece of information.

Most common is a tachymetre, which allows you to determine speed over a set distance. A pulsometre scale allows doctors to work out someone's pulse; and so on. While they're not used very much these days, they're a nice throw-back to the original purpose of these accurate instruments, and a cool reminder of the history a dial can hold. One nice twist on this theme is the 'What could you do in 14 seconds' text on Omega's Apollo 13 Silver Snoopy — referencing the crucial role the chronograph played in the Apollo 13 mission.

The next level

Not all dials are about function though. Some very special dials are about absolutely stunning stones. When gems — usually diamonds — are used on a dial, it's typically as hour markers, but the ultimate expression of a gem-set dial has to be pavé. Pavé doesn't refer to the cut of the stone, but rather how the stones are set into the metal of the dial. It takes its name from ‘pavement’, as the stones are set so close together to resemble a solid surface. Well-done pavé requires numerous skills, from the actual jewellery setting to the selection, grading and cutting of the stones. Once you add colour into the equation, that just adds a layer of complexity. And while some after-market stone setters and customisers do fine work on the stone setting, they often fall short when it comes to the quality and consistency of the stones. And when you're looking at a fully set dial, that quality really speaks for itself.

So next time you look down to check the time on your watch's dial, think about all the skill and hard work that went into creating those precious millimetres of watch real estate.