Right from highly complicated pocket watches to exquisite wristwatches with chronos made for the aristocracy in the 1930s, we look at the fascinating history of chronographs at Audemars Piguet

There's something undeniably appealing about the mechanical chronograph. For some of us, a primitive part of our digitally dominated sensibilities loses all sense when confronted by a choice specimen. A watch is, by nature, a simple tool of observation, but it’s the chronograph over most other complications that converts the wearer from a casual observer to an active participant with the simple click of a pusher. Not so long ago, this technology was an essential tool around which the moving parts of an increasingly industrialized society were choreographed. Today, relegated to more or less a novelty, the mechanical chronograph has only strengthened its gravitational pull.

The timeline of watchmaking is dotted with houses that made significant contributions to the advancement of the chronograph. Complicated timepieces have been an integral part of the Audemars Piguet story from the very first days of the company, and it may come as no surprise that the very existence of a brand whose history is punctuated with complicated watches of unparalleled quality came about through a connection born of a shared passion of complicated watchmaking.

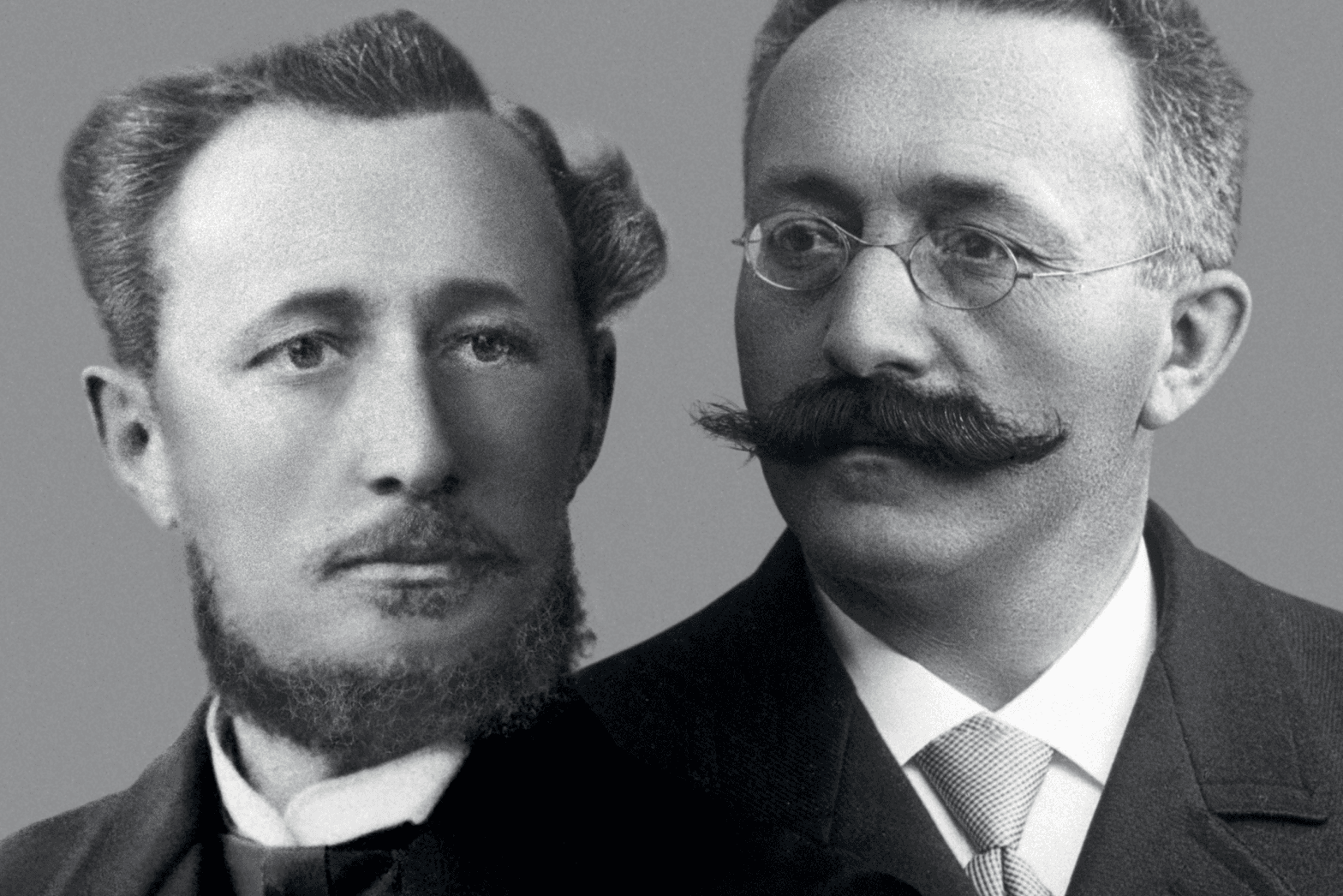

Long before Jules Louis Audemars and Edward August Piguet joined forces, a partnership started in 1875 and consecrated in 1881 with the registration of the business, both families had taken up watchmaking as a way to supplement summer farming income and fill what was otherwise idle time during the bleak winter months in the Swiss Vallée de Joux.

In 1811, a member of a separate branch of the Audemars family, Louis-Benjamin Audemars, founded Louis Audemars & Cie as a maker of watches. Upon his death in 1833, the company passed to his sons and remained in family hands until they closed their doors in 1885. One theory offers the possibility that some or all of the crop of 18 movements supplied by Jules Louis Audemars as initial inventory to the joint venture may have come from the workshop of Louis Audemars & Cie., although this rumor could be just that and verification would be nearly impossible. Very little is known about these first watches thanks to a tornado that ripped through the valley and severely damaged the workshop in 1891 — but we do know that each movement made prior to 1890 was an individual creation with its own unique characteristics. No two were alike.

Because of the rich watchmaking background of both founding partners and the unique tapestry of independent specialist shops peppered throughout the Vallée de Joux, the right ingredients were there to enable the young etablisseur to bring to market top quality highly complicated timepieces, an advantage that enabled the company to carve out a name for itself as a purveyor of timepieces of the most exquisite quality in a relatively short period of time.

All of this was done without the advantages of the economies of scale offered by mass production, which had been adopted by many competitors within the Swiss watch industry. As Jules Louis Audemars and Edward August Piguet prioritized quality and craft over quantity and scale, the operation remained modest in size for much of its existence. In 1889 the entire operation consisted of just 10 full time employees. Continued success in the early 20th century saw their ranks grow to 38 full time employees, but because of the economic tumult of world wars and global recessions this number would constrict to 15 employees by 1940.

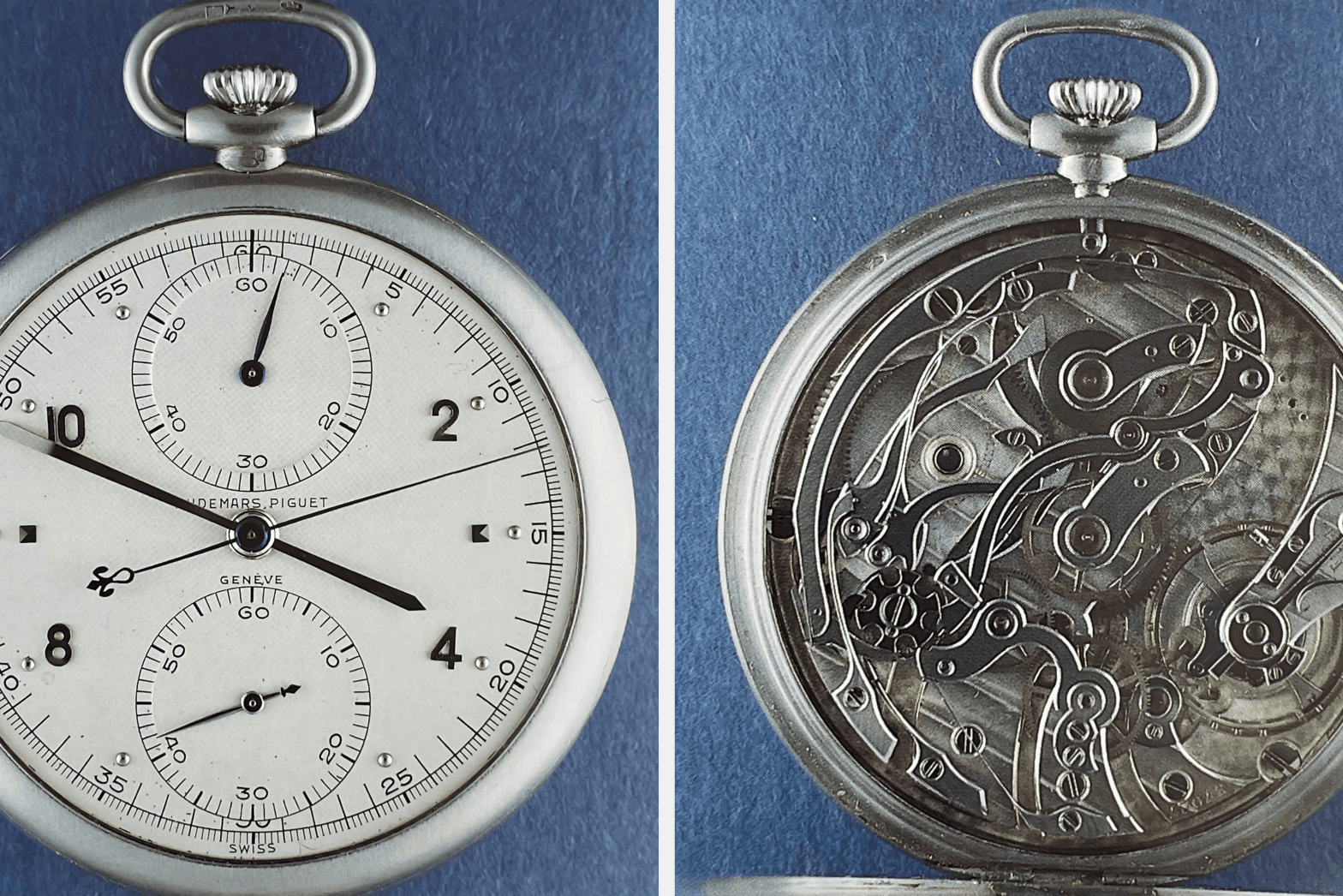

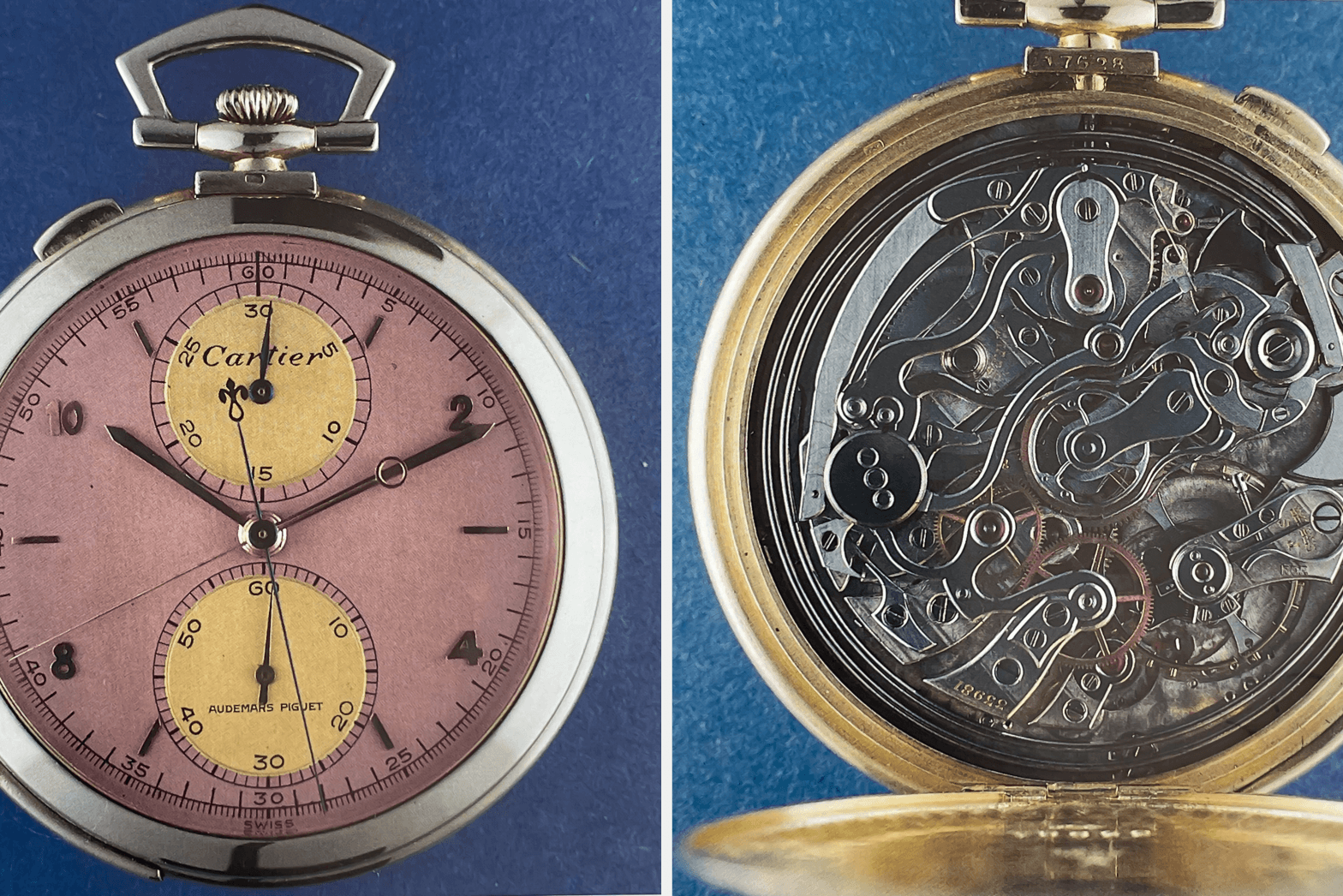

Through the good times and the bad, Audemars Piguet never wavered from the vision of the founders, a commitment to quality that was evident by the who’s-who of society that owned their watches and the retailers that sold them. In addition to well known customers like Tiffany and Cartier, Audemars Piguet supplied watches to Dent and Frodsham in London, Bulgari in Rome, Dürrstein in Glashütte and Dresden and Gübelin in Lucerne.

In 1894, Jules Louis Audemars learned that a split-second chronograph design that Audemars Piguet had patented had potentially been copied by fellow Le Brassus company C. H. Meylan and distributed in North America. After consulting his local agent for North America, Wittnauer, the watchmaker turned sleuth, traveled to New York in search of the offending watch that would prove his case. His suspicions were vindicated when he tracked the suspect watch down in a New York pawn shop. He returned to Switzerland with his prize, physical evidence that demonstrated to a Swiss court his patent was indeed infringed upon.

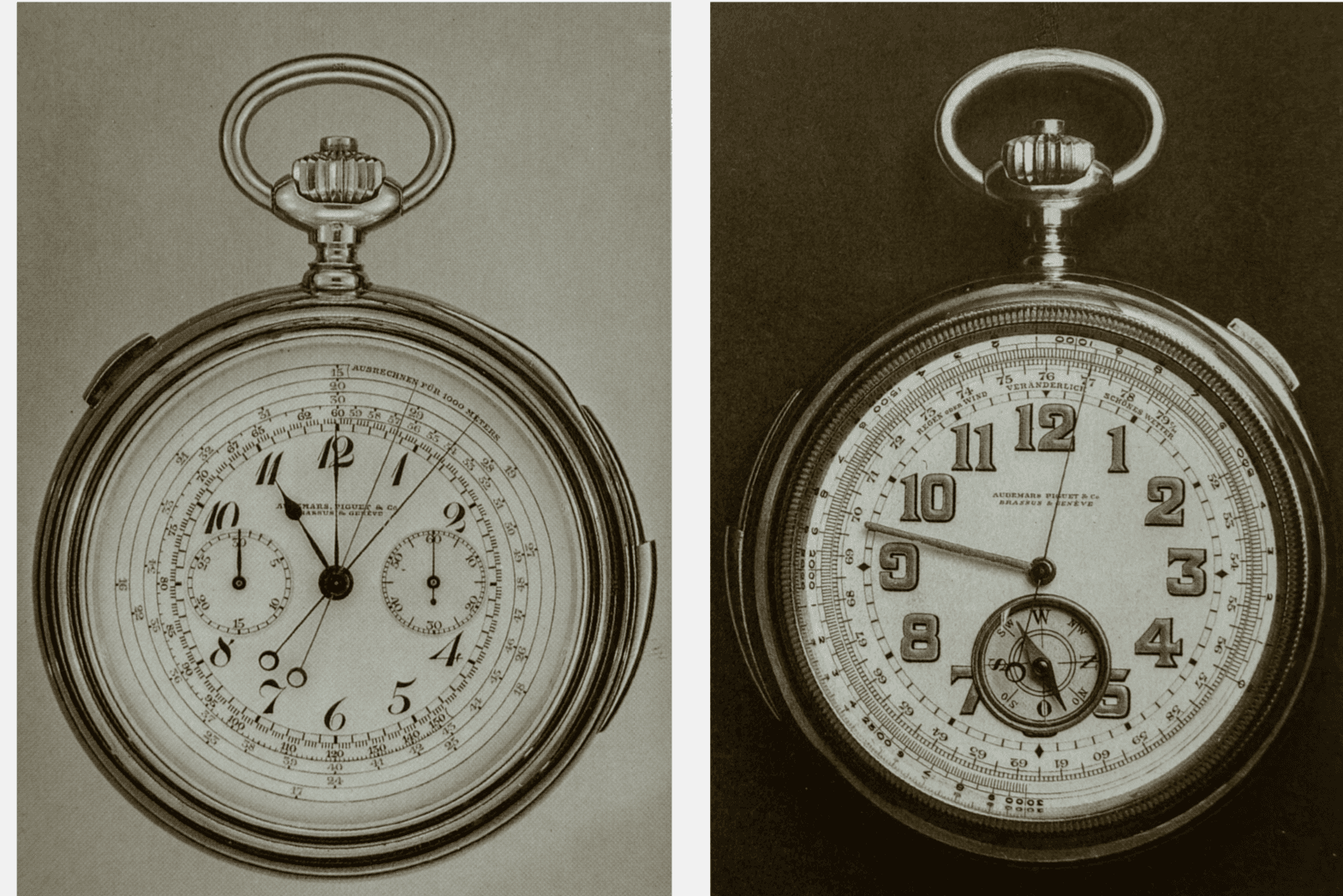

The chronograph played an active role in Audemars Piguet’s offerings from the very beginning. Brunner, Pfeiffer-Belli and Wehrli’s work published in the early 1990’s indicates that between the years 1875 and 1892, AP produced 130 chronographs, 174 split second chronographs, and a multitude of chronographs combined with other complications.

1914 saw Audemars Piguet receive one of the most distinguished and downright interesting commissions of its existence by way of the Emperor of Austria, Franz-Josef I. The Emperor envisioned a watch that combined a pragmatic set of complications—a split-second chronograph with a 30 minute register, an alarm, a dual time zone display, a minute repeater, a barometer, and a compass. However, the imperial commission was by no means the company’s most complicated. Since the early 1880's, Audemars Piguet had poured itself into mastering what it saw as the pinnacle of complicated watchmaking - the Grande Complication. For a watch to be considered a Grande Complication it must necessarily include a minute repeater, a perpetual calendar function, and a split second chronograph in addition to the time.

But times were changing, and the next decade saw the rise in popularity of a new style of watch — the wristwatch. Never one to be caught off guard by the changing winds, Audemars Piguet produced many beautiful wristwatches along side pocket watches during the 1920s. In 1930, they had successfully created their first generation wrist chronograph which was actuated via a single pusher integrated into the crown. Six total of this style movement were produced, one of which was delivered as a wristwatch. By 1933 the chronograph had evolved again, featuring a single chronograph pusher at 2 o’clock that was followed soon after by a dual pusher configuration that allowed the operator to start and stop the chronograph function without resetting the counter. In 1939 Audemars Piguet again enhanced functionality with the addition of an hour counter.

These earliest models were characterized by traditional white enamel dials painted with black Breguet style numerals and small diameter cases in both precious metals and steel. By the end of the 1930s, the enamel dials had mostly disappeared in favor of metal with contemporary Art Deco and Bauhaus design cues.

To power their new wrist chronographs, Audemars Piguet turned to Valjoux’s 13”’ chronograph movement. The earliest movements can be identified at a glance by their gold gilt finish, a process which soon gave way to German silver plating.

What comes as truly remarkable when discussing Audemars Piguet’s vintage chronographs is twofold. First, the company produced only 307 wrist chronographs in total. Second, each of these chronographs was made over a span of 16 years, beginning in 1930 and ending in 1946, a most tumultuous time in Europe and a time during which Audemars Piguet was fighting for its very existence. If this sounds like an extremely small number, it is. Let's also bear in mind that over the 95 years that separated the founding of the partnership from the year 1970, a total of 550 complicated wristwatches were produced. That’s an average of 5.7 complicated watches a year.

Numbers like these help us understand how truly special every complicated vintage Audemars Piguet wristwatch is. Remarkably, less than two decades after the first mechanical wrist chronograph left the bench, the landscape would change yet again. By the late 1940s, chronographs were no longer being made in the modest Le Brassus workshop, and another decade saw the manufacture of complications fade all together as the company switched gears to what they saw as the future — thinner movements, self winding mechanisms, and date complications. It wasn’t until the beginning of the modern era of watchmaking that the perpetual calendar was reintroduced.

Today, the chronograph is again an integral part of the Audemars Piguet lineup, and the 2020 release of the [Re]master01 chronograph, along with the recent opening of their on site museum, proves to even the harshest critic that the Audemars Piguet of today isn’t some half-baked dinosaur wrapped up in a hexagonal love affair, but a watchmaking megalith focused on cultivating its rich past in a way that connects to the modern collector.

![The [Re]master01 chronograph released in 2020 and inspired by the pre-model 1533](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwc-strapi.s3.ap-east-1.amazonaws.com%2Farticle_import%2Fimages%2F142%2F593A3253_1.jpg&w=4320&q=75)