Understanding The Hidden Appeal Of The Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso

Elegant, discrete and in many ways ahead of its time, we look back at one of the most influential shape watches of the 20th century – and reveal why you should be collecting them

It’s likely only a small exaggeration to call the Reverso one of the most underrated watches of the 20th century. Out of circulation for decades following the conclusion of WWII, Jaeger-LeCoultre’s iconic double-sided design has always tended to appeal to a very niche subset of the watch community. Historically, these aren’t collectors who fret much about their watch’s desirability among celebrities; nor are they those for whom ROI is a must-have when chasing new acquisitions.

This means that, despite decades of nurturing from within JLC itself, the Reverso remains something of a horological dark horse. For those keen to unearth what remains of watch culture’s so-called hidden gems, one might even boast that the Reverso offers collecting opportunities – whether vintage or modern – now largely absent in the world of Cartier – an obvious point of comparison when it comes to classic shape watches. Cutting to the chase: if you have an itch for design classics that acquit themselves equally well in the arena of fine watchmaking, then the Reverso flips between the two seamlessly whilst offering something that, for most watch brands in 2022, remains in short supply. Subtlety.

Rise And Revival: The Reverso’s 20th Century History

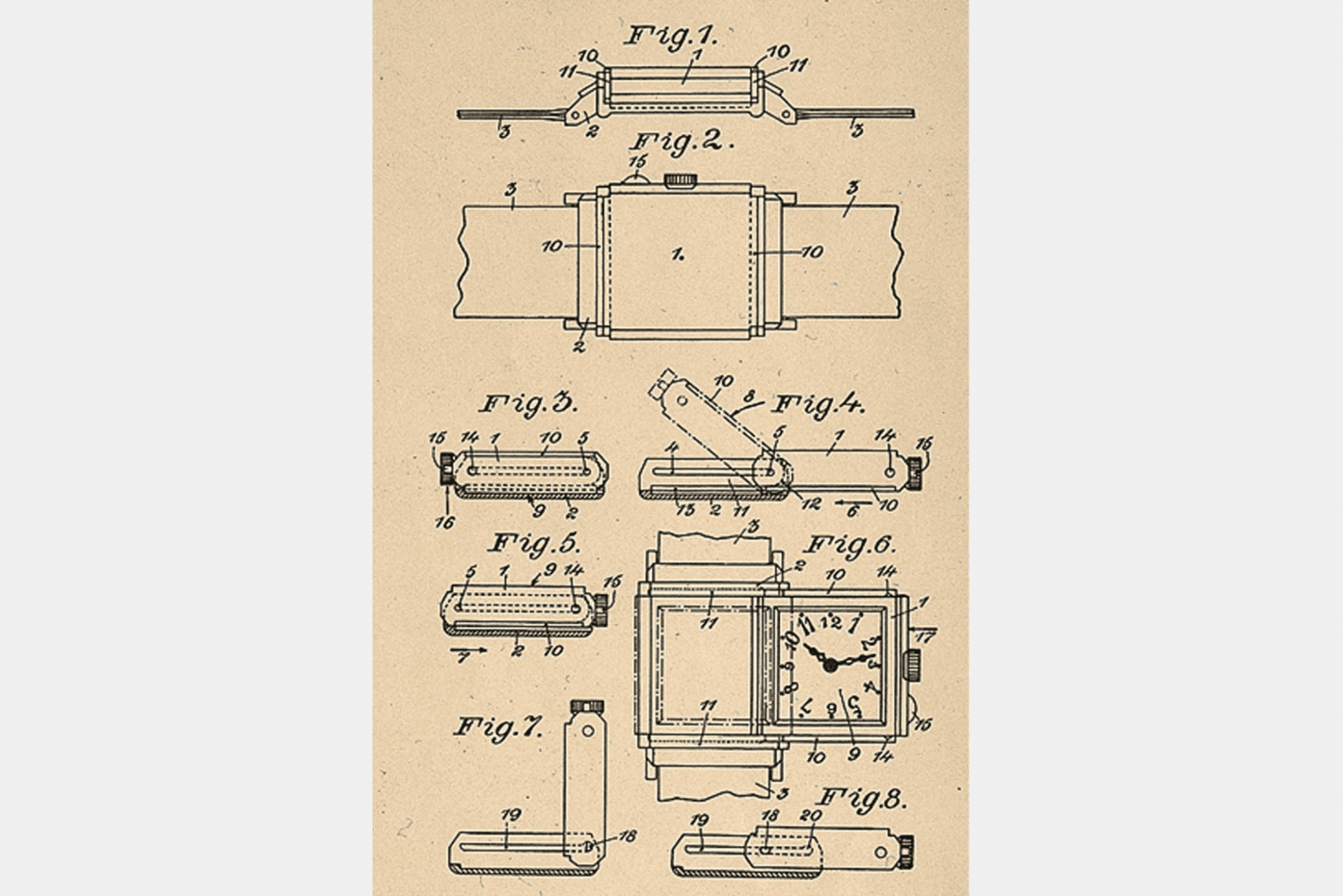

To appreciate just how vital the quality of understatement is to the Reverso, it’s first necessary to time-travel back to 1930s India. Conceived for players on the polo fields of the British Raj (in need of a timepiece with superior protection) the Reverso drew upon the combined expertise of three men: French engineer Rene-Alfred Chauvot, who designed the unique case architecture; Jacques-David LeCoultre, tasked with supplying mechanical movements; and (most famously) Cesar de Trey, a Swiss business magnate credited with the original idea for a watch “capable of sliding in its support and being completely turned over”.

European patents were filed soon after de Trey returned from India, but it wasn’t until 1933 that LeCoultre managed the somewhat trickier feat of outfitting the Reverso with an in-house movement. In fact, in order to bring the watch to market more quickly, the earliest productions (1931-32) were made with ébauches supplied through Tavannes—explaining why many examples during this period are simply signed ‘Reverso’. Jaeho Chang, a noted collector of historic Reversos, finds these tidbits to be particularly charming, given JLC’s modern reputation as ‘the watchmakers’ watchmaker’. “The fact that [the brand’s] most iconic watch originally used a third party movement is a fun reminder of how differently things were done in the vintage era” he says. Equally, the Reverso’s then cutting-edge design made it popular with other brands. Akin to vintage iterations of the Tank, today it’s possible to collect a number of authentic Reversos co-branded and sold during the 1930s by such marques as Patek Philippe, Vacheron Constantin and, most amusingly of all, Cartier.

Beyond the Reverso’s associations with European elites, the design is equally celebrated for its gentle evocation of the Art-Deco – inspired by the same “abandon calculated to stimulate popular fantasy” present in edifices like The Chrysler Building. The emancipation of women in 1930s America also meant that female customers became a driving force of the Reverso’s early success. The triple-gadron design – which had evolved somewhat since the days of de Trey’s first patent – was well-suited to configuration as a necklace or pendant; thus allowing it to sit comfortably alongside the audacious Jazz Age fashions of the time. Today, much of the art and apparel from that era feels chintzy, yet the Reverso maintains its contemporary edge – elevating it to that sparsely populated category of classic design reserved for things like the Porsche 911 or LC2 armchair.

Unfortunately, as the spectre of WWII loomed, demand for the Reverso came to a standstill. Like any other watchmaker operational during that era, JLC (as it would become known after 1937) spent the vast majority of the pre and post-war years making military-specification timing instruments. As Nicholas Foulkes, historian and author of Reverso reveals, by WWII’s end appetites for the eponymous watch had waned so spectacularly that it was discontinued in 1948 – the last time collectors would see it for 24 years. Worse still, scientific advancements had rendered the Reverso’s original purpose obsolete, as Foulkes explains: “The new world that had been forged in the hellish furnace of a global war…had scant space for polo-playing dilettantes. The vulnerability of watch glasses disappeared with the arrival of first acrylic then synthetic sapphire crystals, rendering the once-elegant gesture of flipping over the watch on one’s wrist a redundant affectation.”

The Reverso’s story could very well have ended there, had it not been for the daring intervention of the Italian market. In the early 1970s, the Swiss watch industry was once again confronted by the very real threat of obsolescence: following WWII, Japan’s rapid reemergence as a global economic power brought with it the innovation of quartz technology; and European brands were scrambling to adjust to this new reality of low-cost, mass-manufactured accuracy. Various strategies were employed to compete with the Japanese directly, but a handful of companies (e.g. Audemars Piguet) embraced a contrarian approach that emphasized the beauty and scarcity of mechanical watchmaking. Whether they knew it or not, JLC’s executives at the time were doing just that when they agreed to sell their entire inventory of unfinished Reversos to a man by the name of Giorgio Corvo.

An astute industry observer who also happened to be JLC’s representative in Italy, Corvo wagered a revived Reverso would sell well among Italian collectors – regarded as being “hugely influential in setting horological trends” of that era. The 200 empty cases (which JLC subsequently agreed to retrofit with ovoid movements) were the means by which he proved his calculus: within a month, every single one had been sold – an explosive result, considering that ‘200’ was the number of Italian sales JLC expected to do per year. Galvanized into action by Corvo, JLC brought the Reverso back in short order: reestablishing the original model’s appeal during the late 1970s, before giving it a comprehensive overhaul at the hands of designer Daniel Wild. In 1985, by the time this modernization project was complete (a process Foulkes remarks “[left] the watch mechanically unrecognizable yet simultaneously aesthetically unchanged”) the number of parts employed in the making of a typical Reverso case had more than doubled – from 23 to 55.

Pitfalls And Personas In The Reverso Community

In light of everything that has been said about the Reverso – its deep variety, original design, and historic affiliation with multiple brands – you’d be forgiven for wondering why it isn’t more popular amongst the general watch-buying public. Notwithstanding its more modern incarnations (a flagship collection for JLC these past 20 years), there have been a number of historic hurdles associated with collecting this style. Eric Wind, the eminent watch advisor and founder of Wind Vintage, gives a concise summary: “First, [Reversos] are quite small watches and too small for many people’s tastes. Second, there are not many examples up for sale at any given time, as relatively few were made. Thirdly, of the few examples that come to market, many, if not most, have reprinted/damaged dials and overpolished cases, and thus, aren’t that interesting to collectors.”

In a similar vein to Wind, Chang cautions collectors thinking of getting into vintage Reverso about the risk of swapped parts. “Thankfully, it’s a watch where dial and case swaps aren’t too common,” says Chang, but “one should still… make sure that the case’s serial number is period-correct for the type of movement that is inside – for example, a Lisica movement should not be in a case bearing the ‘25000’ serial”.

Fortunately, even if you take relative scarcity and issues relating to condition into account, the Reverso remains an intriguing proposition for collectors who are happy to do a little digging. “With time and further scholarship,” says Wind, “great vintage Reversos will be recognized as important pieces in world-class watch collections”. This isn’t to say that it does not already have its fair share of halo examples: in a much-publicized auction held by Antiquorum in 2015, the personal Reverso of General Douglas MacArthur hammered for $90,000. Beyond its significant provenance, Wind observes that this model possessed a number of highly desirable dial characteristics: chief among them, a retailer signature and the then-unusual inclusion of lumed Arabic numerals.

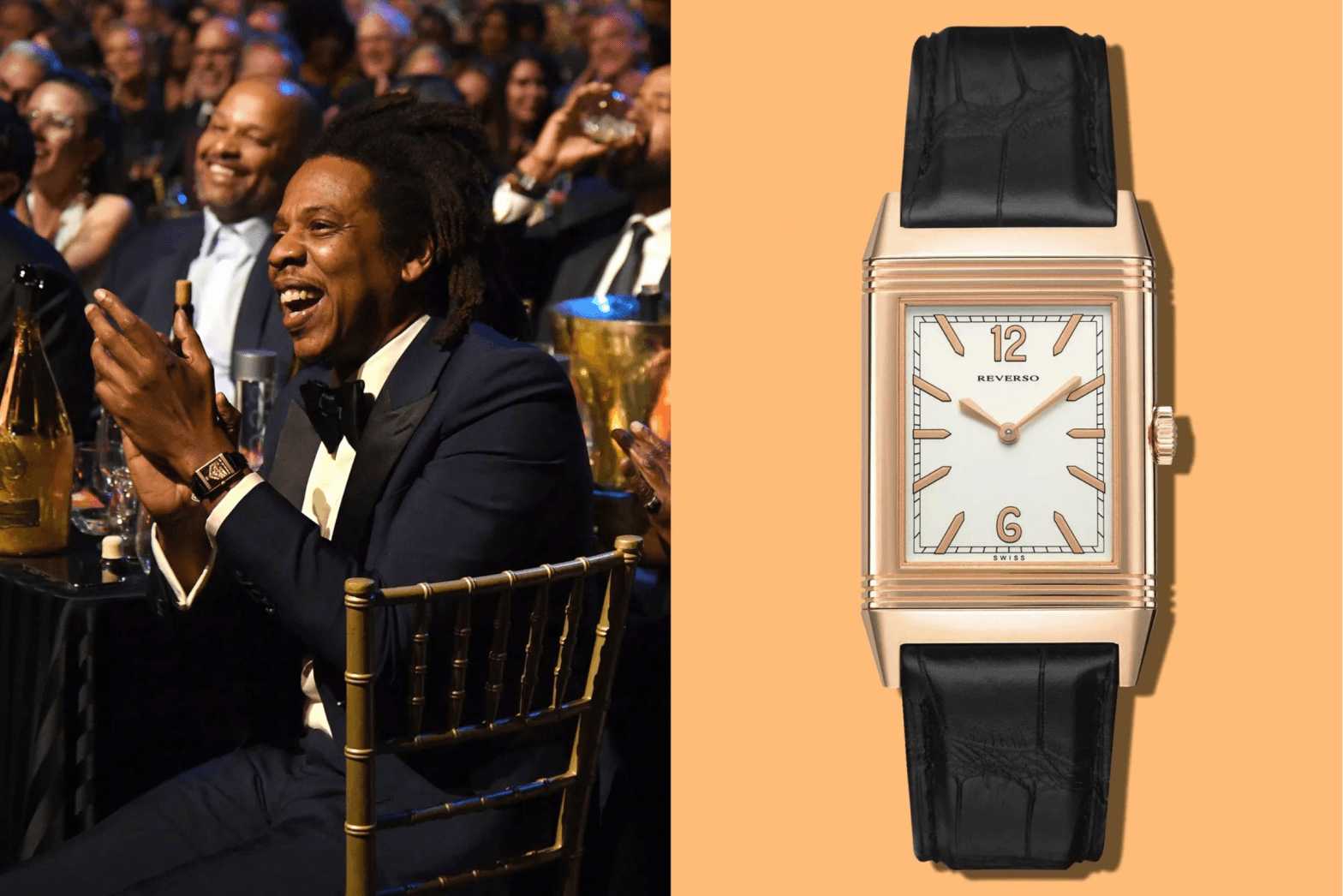

The Reverso’s historic ties to British India and in-built capacity for customization have always made it appealing to aristocrats. In England, the Prince of Wales has been seen sporting the design on numerous occasions; while Clare Mountbatten, Marchioness of Milford Haven, enlisted JLC in the production of a unique, duoface-style model. Indeed, the Reverso’s lofty, authentically patrician airs have even given it devotees outside the British peerage: with a recent example being that of American emcee and mogul, Jay-Z. Inarguably one of hip-hop’s most astute watch collectors (whose horological proclivities extend far beyond ‘Patek Water’ and Richard Mille), Hova chose to celebrate his induction into the 2021 Rock & Roll Hall of Fame with a ‘Tribute to 1931’ – JLC’s modern recreation of the first Reverso. Part of a limited 500-piece edition (“one recently sold for about US$20,000 in an online auction”, says Wind) the Tribute is the physical embodiment of the ‘anti-rapper’ watch; and a fitting choice for an artist whose own work traffics in hidden nuances and subtlety. This speaks to another aspect of the Reverso’s appeal that must be experienced firsthand – its wearability. “I never feel under- or overdressed wearing one of these,” says Chang. “I also love how much of a conversation piece the Reverso is: even non-watch people find the flip mechanism to be fascinating, and that allows me to explain the culture of watch collecting from an unpretentious narrative angle.”

Eternal Canvas: Traditional Artistic Crafts And The Reverso

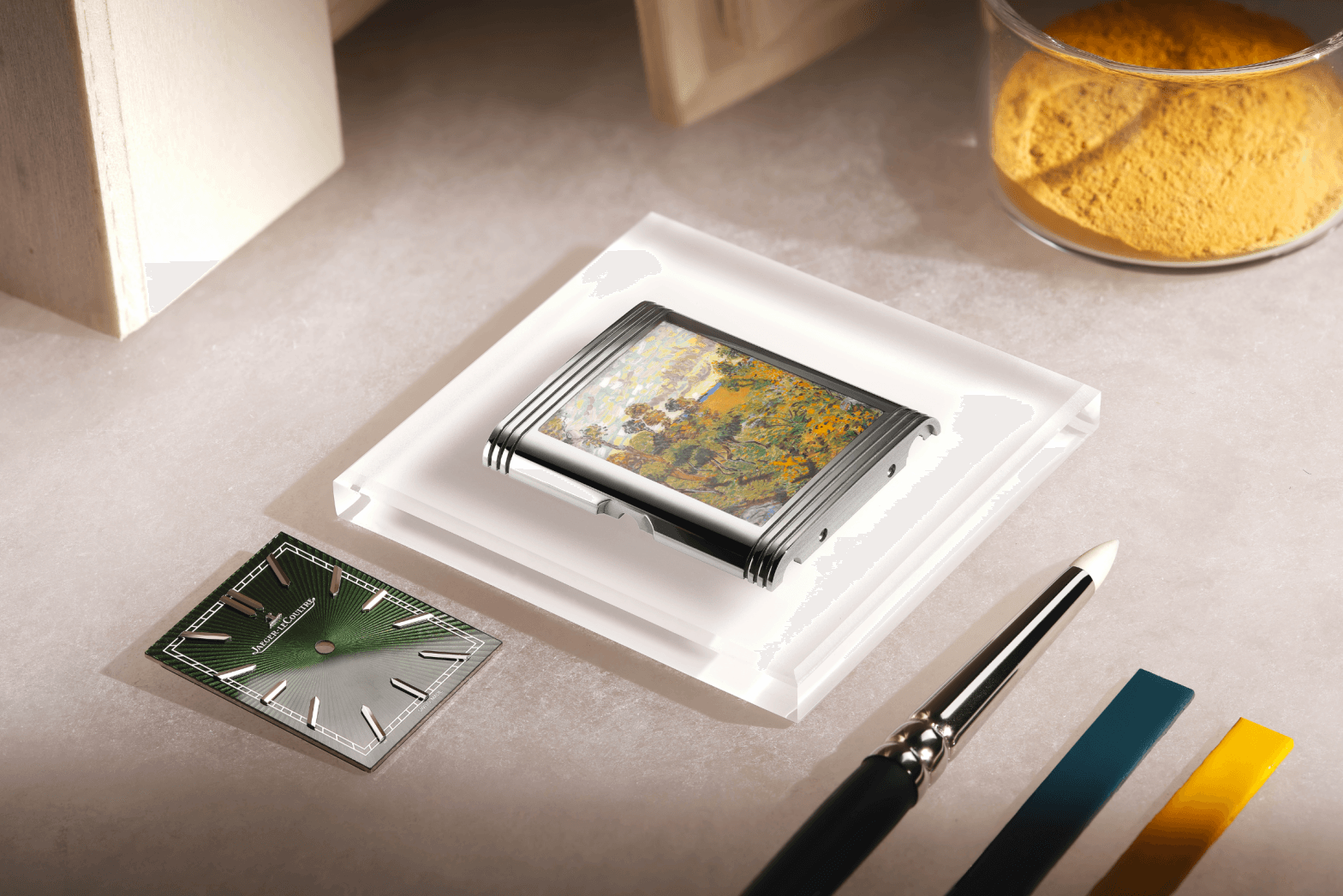

Much of what makes a watch iconic hinges upon how successfully it can incorporate a particular subset of specialist watchmaking. Patek Philippe world-timers, for instance, are as celebrated for their cloisonné enamel dials as they are their namesake complication; and similarly, it’s impossible to explain what makes the Reverso quite so special without also acknowledging its decorative potential.

The Reverso’s unique connection to the world of artistic crafts (chiefly, engravature and enameling) has its roots, at least partially, in history. For the majority of the 20th century, it had always been a time-only watch, in which the most complicated mechanism was the swiveling case architecture. Then, in 1994, using the proportions of the larger more modish Grande Taille, JLC unveiled the ‘Duoface’: a single movement (i.e. the Caliber 854) that exploited the Reverso’s ingenious front-and-back design to display two time zones simultaneously – in effect, the brand’s first travel-centric Reverso. “[It] was a hugely significant model,” says Foulkes, “not least because it was the first mainstream complication to enter the core range of Reversos”.

Thus, as is evident from popular scholarship, the Reverso has only been a complicated watch for a relatively short span of time. This goes some way to explaining why, amongst diehard Reverso collectors, a large contingent have yet to embrace the contemporary examples – masterfully integrating everything from chiming mechanisms to chronographs – as grails. “My two favorite modern Reversos are the minute repeater and tourbillon limited editions,” Chang concedes. “However, complications are not the soul of the Reverso: that, for me, undoubtedly encompasses rare métiers and special engravings.”

In theory, JLC only began consolidating an in-house studio for enamel artists in 1996—under the direction of the brand’s self-taught prodigy Miklos Merczel—however, there are numerous records of Reversos with enamel-painted casebacks going all the way back to the 1930s. Pieces such as the ‘Indian Beauty’ (allegedly depicting Panna noblewoman Kanchan Prabha Devi) represent JLC’s early forays into the artform: today, the company employs more than half a dozen full-time enamel painters, who are skilled enough to adapt various different national painting techniques to the Reverso’s diminutive scale. Works that have been applied to Reversos notably include Georges Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884); Xu Beihong’s Galloping Horses (1946); and Under the Wave off Kanagawa (circa 1832) by Katsushika Hokusai.

The expertise and intensely long hours needed to create miniature enamels mean that – putting aside the question of financial feasibility – Reversos painted in this manner are a rarity. Conversely, the etching of dates, initials, or some other form of personalized information is a service offered by almost all watch brands, but once again, proves uniquely important to the world of Reverso collecting. Put simply, unlike other watches, the Reverso’s caseback can be rotated for the viewing pleasure of the wearer and those in their vicinity at any time—transforming, in an instant, how any attendant engravings are perceived.

The practice of engraving Reversos finds strong precedence in the military, with these examples often connected to storied fighting units which have now been amalgamated or were otherwise lost to history. One extremely cool example was brought to our attention by Wind: a Ref. 201 Reverso made in 1933, cased in yellow gold, with an enameled engraving of the Royal Berkshire Regiment’s ‘China Dragon’ crest. This unit of British line infantry distinguished itself in an array of conflicts during WWI and WWII; really driving home how interesting provenance is at the heart of Reverso collecting. “True elegance lies in discretion,” says Chang. “The fact that such engravings are hidden—and that one needs to consciously decide to flip the watch to display them—elevates their meaning—no watch is a better canvas for personalization.”