The Most Important Modern Chronograph Movements (Part 1)

What does it take to produce a great chronograph? A lot. We explore the making of the most significant chrono movements in the 21st century

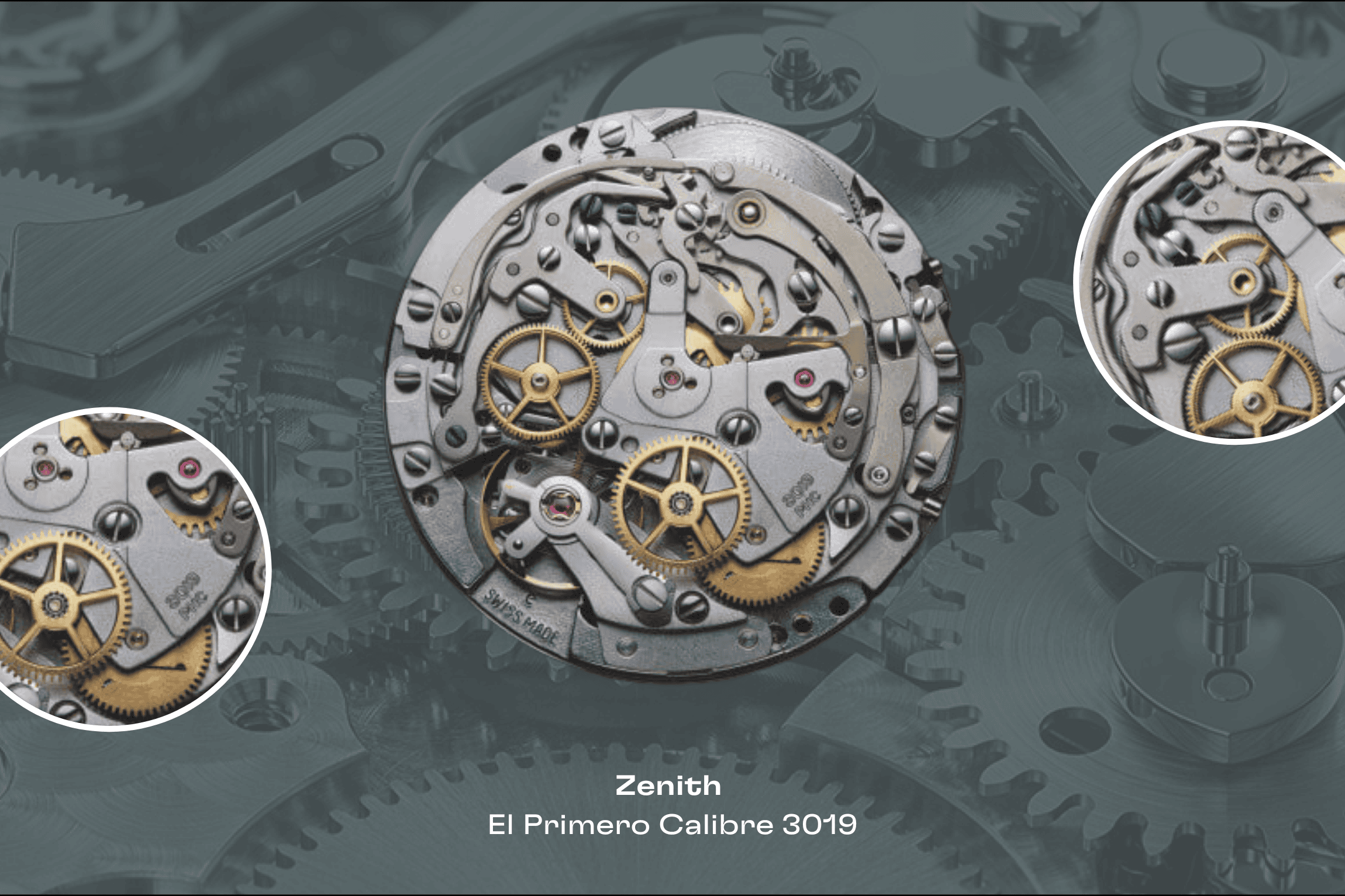

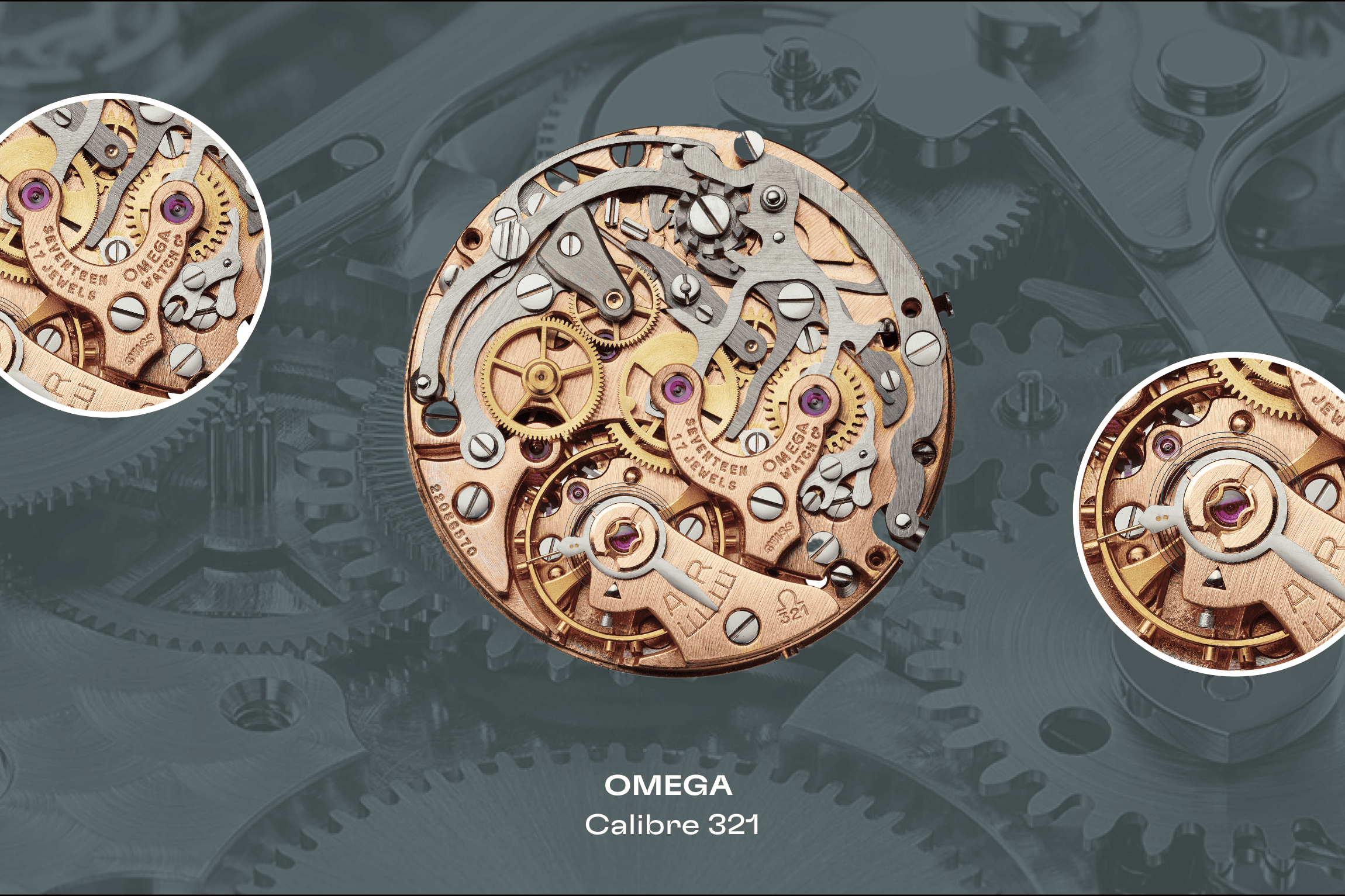

Chronographs are, without a doubt, amongst the most popular complications in watchmaking, offering both practical functionality and wrist appeal.Given this enduring popularity, it's perhaps surprising how many new and current production chronographs are built off designs that are more than half a century old. Iconic chronograph movements like the Zenith's El Primero and the Calibre 11 were announced in 1969, and the ubiquitous Valjoux 7750 was released in 1974. On the manual-winding front, the Omega Moonwatch you can buy today is powered by a movement that is fundamentally the same design as the Calibre 321, which dates from 1946, and is itself based on the Lemania 2310.

Chronographs are, without a doubt, amongst the most popular complications in watchmaking, offering both practical functionality and wrist appeal.Given this enduring popularity, it's perhaps surprising how many new and current production chronographs are built off designs that are more than half a century old. Iconic chronograph movements like the Zenith's El Primero and the Calibre 11 were announced in 1969, and the ubiquitous Valjoux 7750 was released in 1974. On the manual-winding front, the Omega Moonwatch you can buy today is powered by a movement that is fundamentally the same design as the Calibre 321, which dates from 1946, and is itself based on the Lemania 2310.

In fact, the Lemania 2310 is a great case study for the slow rate of innovation in the chronograph space. Lemania's movement debuted in 1942 and stands out for its attractive, elegant design, compact size and sheer versatility. In the decades since, this base design has become a staple, being used by everyone from Patek Philippe and Vacheron Constantin to Roger Dubuis and Franck Muller.

In fact, the Lemania 2310 is a great case study for the slow rate of innovation in the chronograph space. Lemania's movement debuted in 1942 and stands out for its attractive, elegant design, compact size and sheer versatility. In the decades since, this base design has become a staple, being used by everyone from Patek Philippe and Vacheron Constantin to Roger Dubuis and Franck Muller.

A similar story can be told about all the other great legacy movements, which have been adapted and reused by an entire industry. The reason is, of course, simple. Developing a brand-new chronograph movement from the ground up is an expensive and time-consuming endeavor. It's much easier and just as effective to lean on designs which have proved themselves over decades. There's a reason that some of the most established chronograph makers (Breitling, Heuer, Hamilton-Büren and Dépraz & Co) have to team up to develop the Calibre 11.

This is the real reason why you can count the number of new, commercially produced chronograph movements on one hand. So it's worth celebrating those mighty few who have walked the path of developing new workhorse chronograph movements for the 21st century.

Few chronographs can match the Rolex Daytona for cachet and coolness, but it might come as a bit of a surprise to learn that the brand relied on externally sourced chronographs until it developed the Calibre 4130 in the year 2000 — the first time the Crown made a chronograph of their own. Prior to this, the brand relied on the venerable El Primero to keep the mighty Daytona ticking. It's worth remembering that in the 90s, when this calibre was in development, Rolex was in the midst of an ongoing push to bring everything under one roof. CEO Patrick Heiniger was busy acquiring the brand's long-standing suppliers to give the brand ever greater control over production and quality. This ethos of simplicity and reliability is apparent in the Calibre 4130, which had around 20 per cent fewer components than the El Primero but was more efficient and reliable. It's a chronograph, the Rolex way. As a side note, it's worth noting that it was only earlier this year that Rolex retired the Calibre 4130, replacing it with the Calibre 4131, which added in the Chonergy escapement, Paraflex, as well as an open rotor, amongst other incremental improvements.

A similar story can be told about all the other great legacy movements, which have been adapted and reused by an entire industry. The reason is, of course, simple. Developing a brand-new chronograph movement from the ground up is an expensive and time-consuming endeavor. It's much easier and just as effective to lean on designs which have proved themselves over decades. There's a reason that some of the most established chronograph makers (Breitling, Heuer, Hamilton-Büren and Dépraz & Co) have to team up to develop the Calibre 11.

This is the real reason why you can count the number of new, commercially produced chronograph movements on one hand. So it's worth celebrating those mighty few who have walked the path of developing new workhorse chronograph movements for the 21st century.

Few chronographs can match the Rolex Daytona for cachet and coolness, but it might come as a bit of a surprise to learn that the brand relied on externally sourced chronographs until it developed the Calibre 4130 in the year 2000 — the first time the Crown made a chronograph of their own. Prior to this, the brand relied on the venerable El Primero to keep the mighty Daytona ticking. It's worth remembering that in the 90s, when this calibre was in development, Rolex was in the midst of an ongoing push to bring everything under one roof. CEO Patrick Heiniger was busy acquiring the brand's long-standing suppliers to give the brand ever greater control over production and quality. This ethos of simplicity and reliability is apparent in the Calibre 4130, which had around 20 per cent fewer components than the El Primero but was more efficient and reliable. It's a chronograph, the Rolex way. As a side note, it's worth noting that it was only earlier this year that Rolex retired the Calibre 4130, replacing it with the Calibre 4131, which added in the Chonergy escapement, Paraflex, as well as an open rotor, amongst other incremental improvements.

While the chronograph has always been a small part of Rolex's overall offering, the same cannot be said of Breitling, a brand largely built on its expertise in chronographs. So it should come as no surprise that the brand, which has largely relied on third-party ebauches. This changed in 2009 when Breitling unveiled the B01, a thoroughly modern calibre that is produced in a custom-built facility. With modular construction for simpler servicing and a relatively slender 7.2mm height, this impressive movement offers 70 hours of power reserve and an efficient vertical clutch. It's finished in an industrial manner, which is entirely appropriate given Breitling's price point. Interestingly enough, a modified version of this calibre can be found in Tudor's Black Bay Chronographs as part of a movement-sharing partnership announced in 2017.

While the chronograph has always been a small part of Rolex's overall offering, the same cannot be said of Breitling, a brand largely built on its expertise in chronographs. So it should come as no surprise that the brand, which has largely relied on third-party ebauches. This changed in 2009 when Breitling unveiled the B01, a thoroughly modern calibre that is produced in a custom-built facility. With modular construction for simpler servicing and a relatively slender 7.2mm height, this impressive movement offers 70 hours of power reserve and an efficient vertical clutch. It's finished in an industrial manner, which is entirely appropriate given Breitling's price point. Interestingly enough, a modified version of this calibre can be found in Tudor's Black Bay Chronographs as part of a movement-sharing partnership announced in 2017.

Omega is another maker with a long history in chronographs, and more recently, the brand has proven itself to be an industry leader when it comes to movement manufacturing, thanks to their proprietary Co-Axial calibres, as well as the robust and demanding METAS certification. Calibre 9300, which debuted in 2011, was a fully in-house creation, boasting the famed co-axial escapement, as well as a silicon balance spring. Like most more modern chronographs, it uses a column-wheel chronograph with a vertical clutch rather than a cam for more precise actuation. The METAS-certified version of this design is the 9900/9901.

Omega is another maker with a long history in chronographs, and more recently, the brand has proven itself to be an industry leader when it comes to movement manufacturing, thanks to their proprietary Co-Axial calibres, as well as the robust and demanding METAS certification. Calibre 9300, which debuted in 2011, was a fully in-house creation, boasting the famed co-axial escapement, as well as a silicon balance spring. Like most more modern chronographs, it uses a column-wheel chronograph with a vertical clutch rather than a cam for more precise actuation. The METAS-certified version of this design is the 9900/9901.

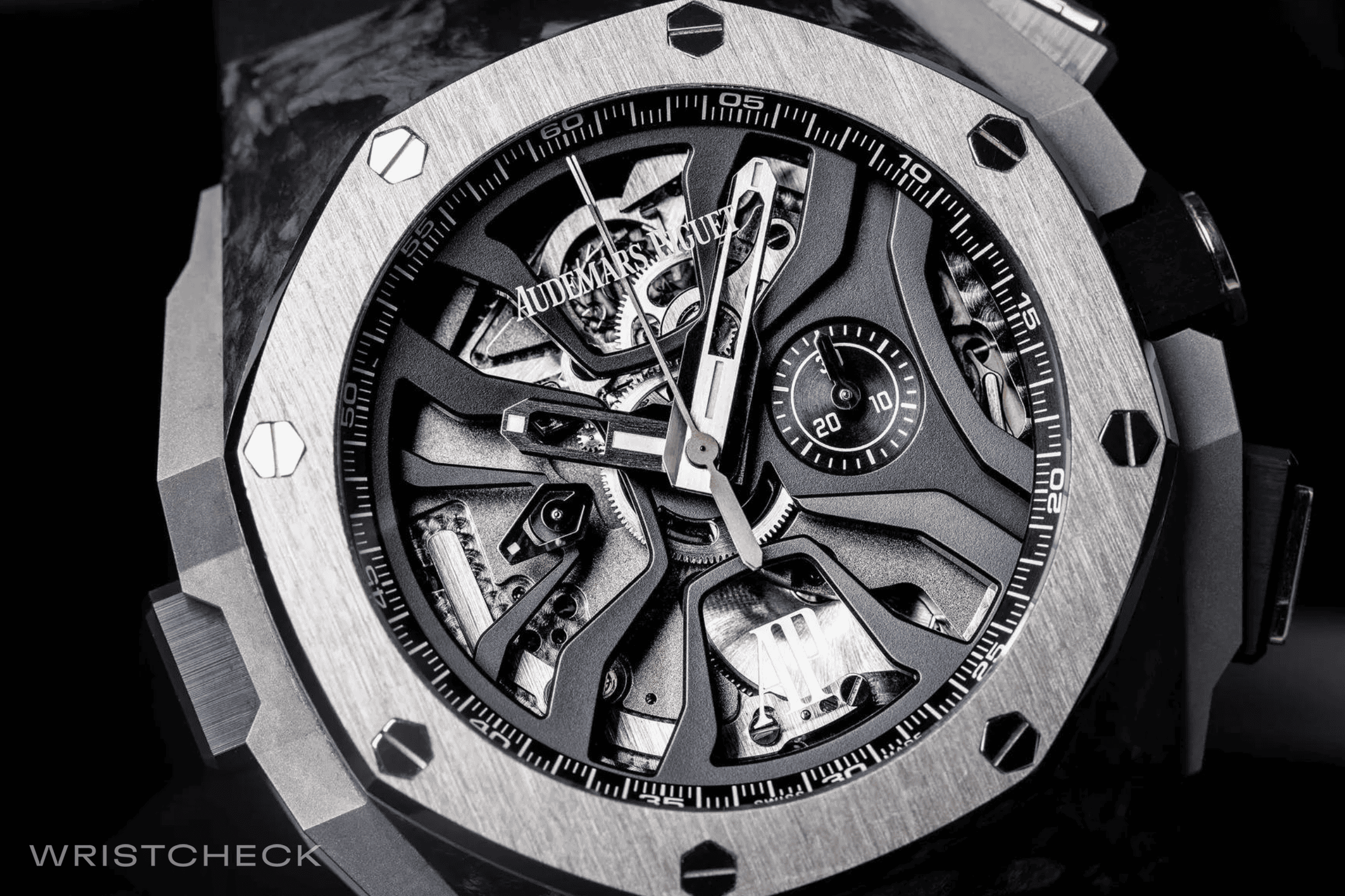

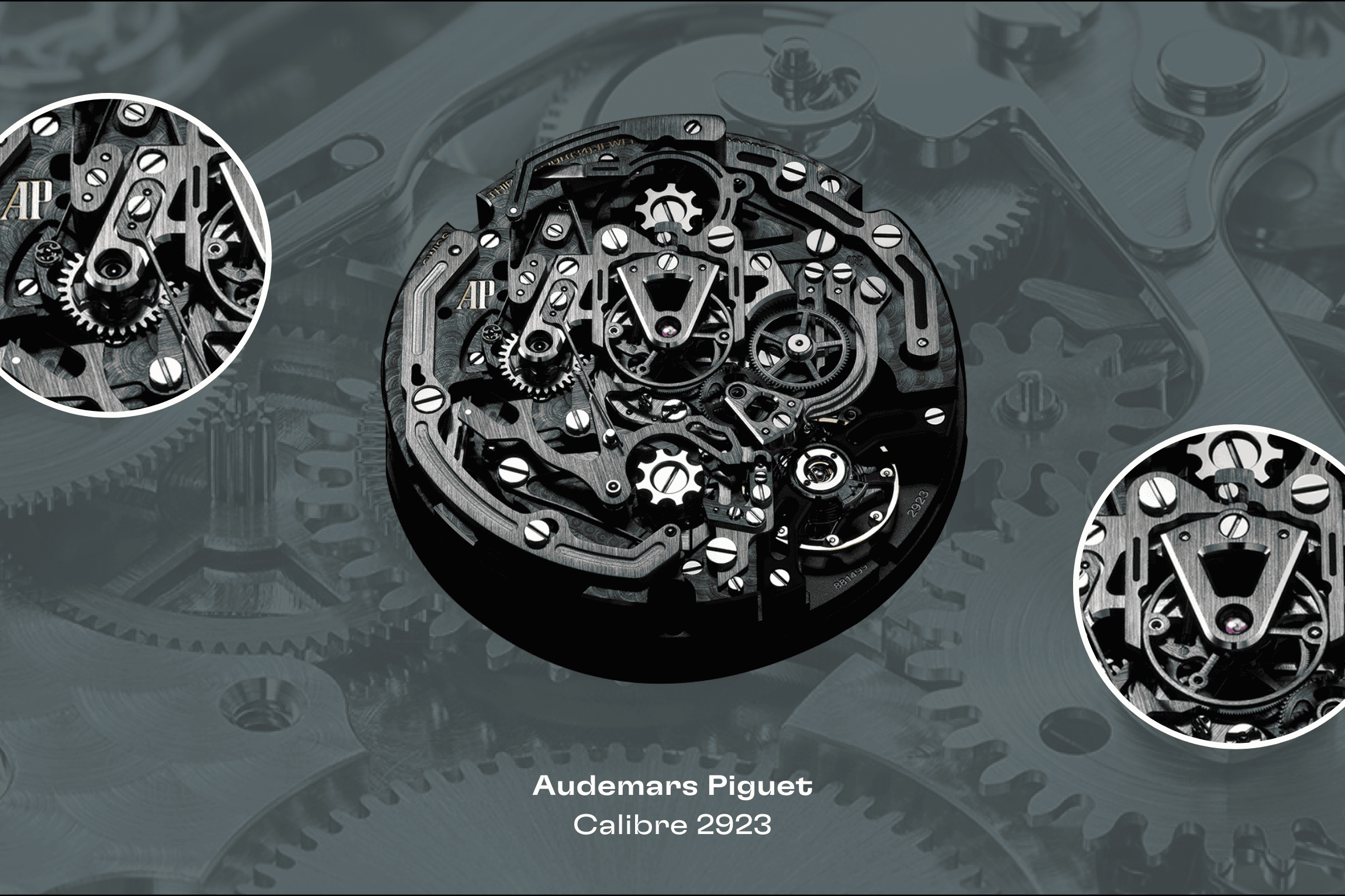

The overarching themes of commercially produced, contemporary chronograph calibres are reliability and simplicity, which makes sense because, as far as complicated movements go, chronographs are — well — complicated. One maker that excels at more complicated watches is, of course, Audemars Piguet. Take for example the Royal Oak Concept Laptimer Michael Schumacher (featuring the AP Calibre 2923), a pioneering piece of engineering that debuted in 2015, and features a split-second chronograph, both of which can be controlled independently via the three pushers. While this heroic work of watchmaking is a high-concept masterpiece, it also represents one extreme of what the brand is capable of. As an example of Audemars Piguet’s more commercial chronograph expertise, look no further than the Caliber 4401. This movement was initially released in the Code 11.59 Chronograph, and has started to be seen across the catalogue. As befitting the brands reputation, the visual appeal of this is top notch with an impressive level of finish on practically every surface, which makes this multilayered movement exceptionally handsome. Of course, polish aside, it's every bit as efficient as its peers, with a flyback mechanism with a column wheel and vertical clutch, and the now standard 70 hours of power reserve.

The overarching themes of commercially produced, contemporary chronograph calibres are reliability and simplicity, which makes sense because, as far as complicated movements go, chronographs are — well — complicated. One maker that excels at more complicated watches is, of course, Audemars Piguet. Take for example the Royal Oak Concept Laptimer Michael Schumacher (featuring the AP Calibre 2923), a pioneering piece of engineering that debuted in 2015, and features a split-second chronograph, both of which can be controlled independently via the three pushers. While this heroic work of watchmaking is a high-concept masterpiece, it also represents one extreme of what the brand is capable of. As an example of Audemars Piguet’s more commercial chronograph expertise, look no further than the Caliber 4401. This movement was initially released in the Code 11.59 Chronograph, and has started to be seen across the catalogue. As befitting the brands reputation, the visual appeal of this is top notch with an impressive level of finish on practically every surface, which makes this multilayered movement exceptionally handsome. Of course, polish aside, it's every bit as efficient as its peers, with a flyback mechanism with a column wheel and vertical clutch, and the now standard 70 hours of power reserve.

It's no surprise that the last 20 years have seen the major watchmakers develop their own chronograph movements, and it reflects the increasing importance of in-house watchmaking. There's also a range of higher-end makers innovating and pushing the boundaries of what a chronograph can do, but we'll discuss that in part two.

It's no surprise that the last 20 years have seen the major watchmakers develop their own chronograph movements, and it reflects the increasing importance of in-house watchmaking. There's also a range of higher-end makers innovating and pushing the boundaries of what a chronograph can do, but we'll discuss that in part two.

Frequently Asked Questions

In chronograph watches, the central second hand is used for the stopwatch function and does not move unless the stopwatch feature is engaged.

The most common chronograph movement is the Lemania 2310, which has been widely adapted and used by various brands including Patek Philippe, Vacheron Constantin, Roger Dubuis, and Omega.