The Most Important Decades in Modern Watchmaking (Part 3: The 2000s)

Step back into the era of triumph and optimism with the coolest watches of the 2000s - think silicon, large sizes, and indie brands. From over-the-top designs to timepieces that pushed the boundaries of creativity, we explore the decade's exuberance and innovation

New year, new millennium and a whole lot of new watches. If the 80s and 90s were decades defined by trial and tribulation, the 2000s were the era of triumph. Watches were unashamedly cool and over-the-top, echoing the era of optimism, exuberance and innovation that permeated culture as a whole. The 2000s gave the world the smartphone, countless box office franchises and skinny jeans. The 2000s gave the watch world silicon, large sizes and exciting new independent brands.

Mr Büsser's Opus

Independent watchmaking, as we know it today, was born in the 1980s. In the 1990s, it developed significantly, with many of the legends of independent matchmaking making a name for themselves during this turbulent decade. The decade after the millennium saw independent watchmaking mature. While there are many names in the bustling independent scene of the 2000s that are worth highlighting, three names come up again and again. Harry Winston, Opus and Max Büsser. Looking back through 2023 eyes, the pairing of MB&F founder Max Büsser and the blue-chip diamond brand Harry Winston might seem like an unconventional one, but in the wild days of the early 2000s, the then 31-year-old Büsser was the CEO of Harry Winston Rare Timepieces. Büsser's key contribution to Harry Winston was the Opus series, an ultra-exclusive limited collection made in open collaboration with pioneering independent watchmakers.

In 2001, the series got off to a flying start, creating six different watches in partnership with François-Paul Journe. This impressive debut was followed up by Antoine Presziuso in Opus 2, and the legendary Vianney Halter in Opus 3, with a simple-yet-sophisticated digital display. In an example of just how bleeding edge this watchmaking was, the Opus 3 was initially launched in 2003, but the delivery of the 55 pieces didn't begin until 2010. After being somewhat burnt by the Opus 3 ordeal, the fourth edition partnered with Christophe Claret for 4, and then with Urwerk's Felix Baumgartner for Opus 5. In 2005, Büsser left Harry Winston to found MB&F, but the Opus series continued until 2015's Opus 14, and continued to provide a platform for some of the most astounding feats of horological ingenuity watchmaking has seen.

Beyond that, Opus — in many ways — served as a proving ground for MB&F, in which Büsser took the values of extreme ingenuity and friendly collaboration and dialed them up to 11. In the process, MB&F, which launched its first Horological Machine in 2007, became the most visible name in independent horology. If pioneering figures like Philippe Dufour, Roger Dubuis and François-Paul Journe serve as the founding fathers and elder statesmen of the Indies, then surely Max Büsser is the movement's ambassador to the wider world.

Big Pilots, Big Bangs, Big Personalities

The indies weren't the only big thing in 2000s watchmaking. If the decades horological output had to be distilled into one trend, it would be the Big Watch Trend. Building off the ever-increasing popularity of brands like Panerai and models like the ROO, watch cases kept on getting bigger and bigger. For many, 42mm was the bare minimum, 45 was standard and 47 plus was a proper 'big watch'. Everyone was doing it, but none were doing it with quite the chutzpah of industry legend Jean-Claude Biver and his latest project, Hublot.

In 2005, one watch was the talk of Baselworld — a brand new design from Hublot, which, until Biver joined in 2004, had been a fairly niche player in the market. The new design was, of course, the Big Bang, and boy did it live up to its name. Defined by the aesthetic 'Art of Fusion' that saw Hublot juxtapose unconventional materials and finishes, it's hard to overstate the impact the Big Bang had on the landscape of watches. Biver, with his keen marketer's eye read the tea leaves of the watch industry and turned it into a watch that offered it all. The initial Big Bang had it all: an industrial aesthetic with exposed bezel screws, a complicated, layered case, carbon fiber dial and of course, that rubber strap. The Big Bang nailed the mid-noughties zeitgeist, and the watch instantly became the disruptive enfent terrible of the industry. The watch was a phenomenal success in its own right, but it was Biver who made that success happen, thanks to his experience, expertise and a healthy dose of self-confidence.

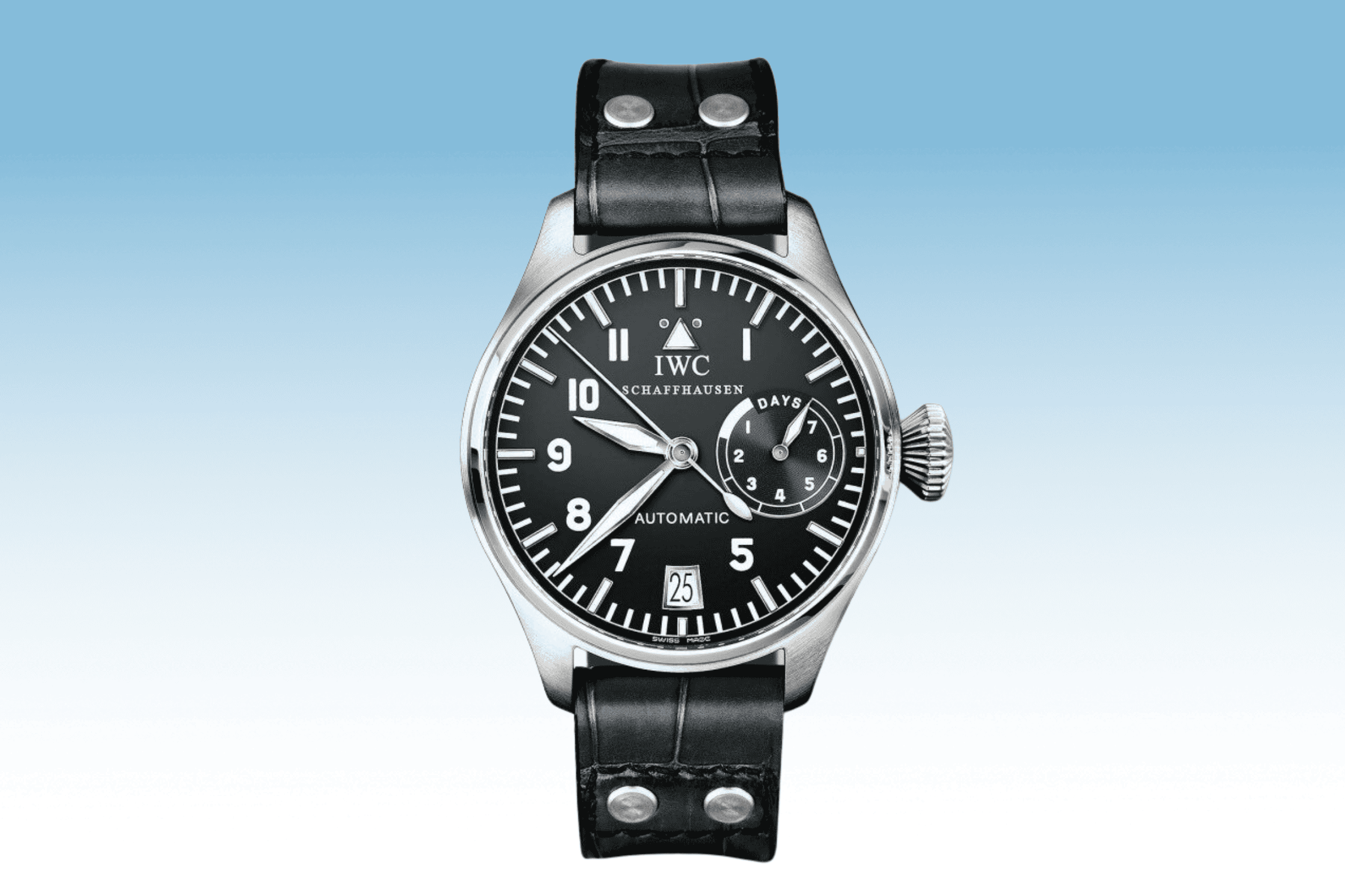

Of course, Biver wasn't the only charismatic leader dominating the watch industry in the 2000s. In 2002, the 32-year-old Georges Kern was announced as IWC CEO and became the youngest Richemont CEO ever. Kern quickly earned a reputation for bold moves and a love of the spotlight, and his leadership was instrumental in putting IWC into the position it is today. His rise coincided with another 2002 debut — the Big Pilot. This military pilot's watch was an oversized, instantly recognizable cult favorite the instant it was released. And while this traditional, vintage design was miles away from the Big Bang style-wise, they had one thing in common, and that's a silhouette that dwarfed most reasonably sized wrists.

Silicon, Whirlwinds and the Crisis

Corresponding to the more-is-more ethos that had come to dominate 2000s-era watchmaking was a sudden preoccupation with an old complication that had come to be seen in a new light: the tourbillon. This nineteenth-century innovation was originally developed to offset the impact of gravity on pocket watches. In the 21st century, it serves no practical purpose. However, this whirling cage of complication did serve as a potent indicator of status. We started seeing dial-side tourbillons in the 80s and 90s, but in the 2000s, that trickle became a flood. The tourbillon became the watchmaking equivalent of an arms race, as brands competed with each other to make ever more technically demanding, precise and impressive versions of this outdated technology. One of the best in the business was Richard Mille. Richard Mille, founded in 1999, offered a completely new vision of watchmaking, resolutely modern and technical. In 2001, the brand introduced their first watch, the RM 001 Tourbillon. Even then the brand was breaking with convention, using a PVD-coated movement and titanium baseplate, as well as a calibre designed by Renaud and Papi. This movement was built for shock resistance and everyday wear. Richard Mille certainly didn't invent the tourbillon, but he went a long way to ensuring it was the go-to complication of the 2000s.

While the tourbillon was old technology, new innovations were emerging. Ulysse Nardin, along with a consortium including Rolex, Patek Philippe and the Swatch Group was exploring the use of silicon hairsprings, which offered numerous benefits in terms of chronometry and anti-magnetism. The first watch to use silicon, was the iconic Ulysse Nardin Freak, released in 2001 which wowed with its movement-as-time indicator design. No less impressive were the silicon escape wheels, a concept that was, at the time, just as freaky as the design. In 2002, patents were filed on silicon hairsprings, and in 2006 Patek Philippe debuted the Spiromax hairspring, with Breguet following soon after. Today, the use of Silicon is far more commonplace, but it stands out as the defining technical innovation of the 2000s.

Up until 2007, the watch industry looked like it was on an ever-upward trajectory. Then, the real world intervened. The 2007-08 Financial Crisis, known widely as the Global Financial Crisis, made its presence felt in the watch industry. While sales saw a marked decline, the bigger impact of the GFC was to curb, for a little while at least, the more hedonistic displays of high-end horology, contributing, in part at least to a more restrained style that would, in the coming decade, see the primacy of the retro reissue and vintage style.