A restoration expert, Pagès is a staunch believer in the art of watchmaking that’s all about the passion, the patience and the precision which goes into crafting handmade watches. To learn more about his philosophy on watchmaking and his first in-house movement, we visited Pagès’ workshop in Les Brenets, Switzerland

For many, independent watchmakers — that broad term for the horological individualists who work their own path, free from corporate restraint — are the industry's rockstars. Virtuoso makers whose rare, finely wrought watches dazzle through a combination of inspired design and hard work.

The established veterans in this space are legends like François-Paul Journe and creative genius of Max Busser, but one of the most exciting aspects of independent horology is that the landscape is constantly evolving, and one watchmaker who is making his presence felt is Raúl Pagès.

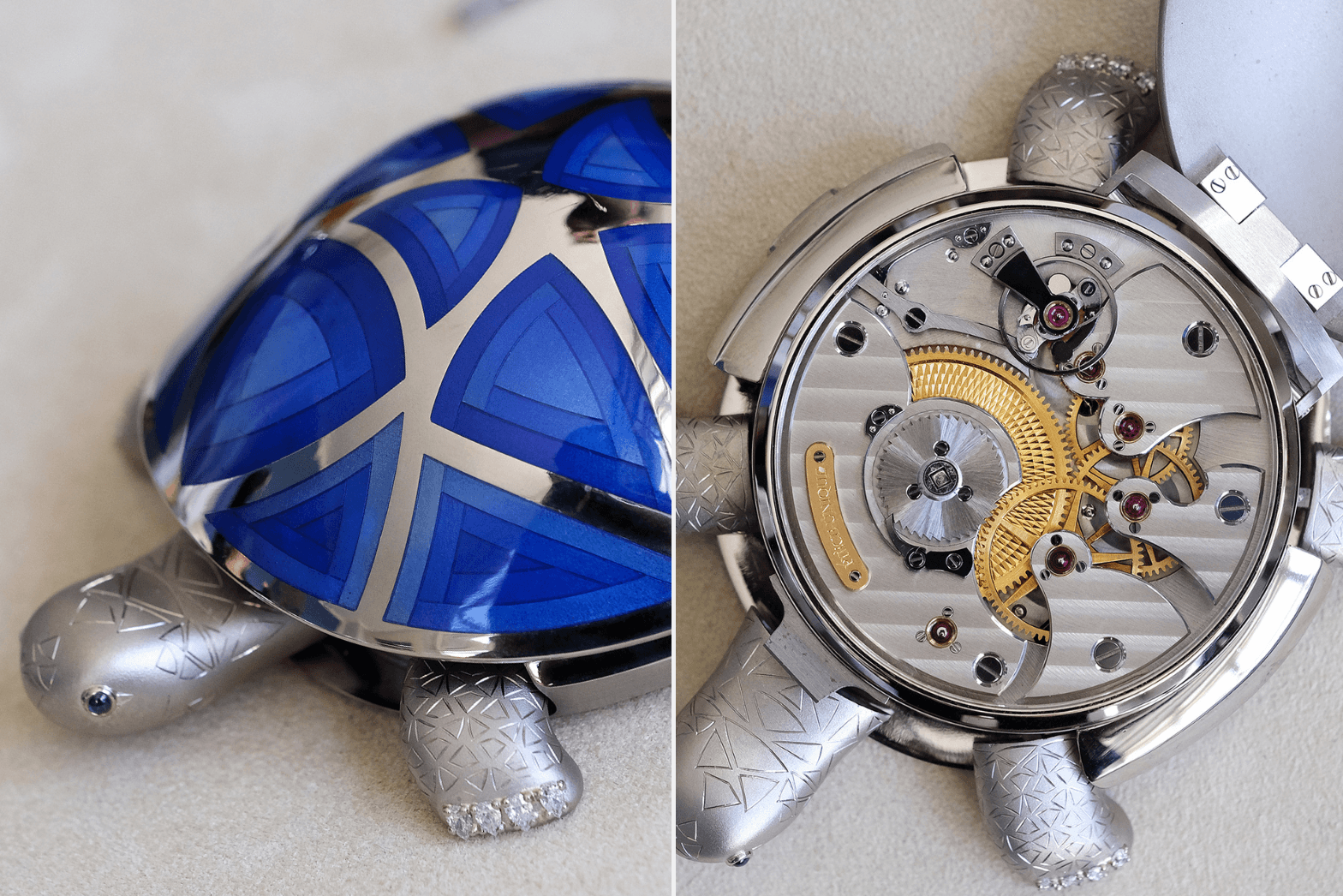

Earlier this year Pagès released, to critical acclaim, his first watch powered with an in-house caliber – the Régulateur à détente RP1 – a sophisticated, aesthetically pleasing, and technically demanding watch that is, in many ways, a love letter to the traditions of precision and chronometry.

The rich heritage of watchmaking permeates more than just Pagès' workshop; it also inspires his own design and technique. Pagès graduated from Le Locle's watchmaking school in 2006. And rather than work on the assembly line of one of the large groups, he, like independent luminaries Kari Voutilainen and François-Paul Journe, began his career restoring antique watches, clocks and automata; first for the well-respected Parmigiani restoration department and later for Patek Philippe. For Pagès, the years of working on decades and centuries-old mechanisms provided opportunities to develop his skills and also his personal philosophy on watchmaking.

"I discovered a lot. Restoration is very interesting because you are working on — if you are lucky like I was — some very beautiful pocket watches and clocks. You see a lot of interesting, different mechanisms and learn from each mechanism. So maybe if I want to develop something new, I will use little bits of this mechanism or that mechanism and so on. You open your mind to a lot of things when you see all these kinds of different systems, and of course, you also learn in a practical way to make components because when you restore a pocket watch from 200 years ago, you cannot just order a replacement part. You've got to learn how they made the wheel and make it from scratch with traditional tools." Also, I can construct movements on a 3D program, I develop everything myself, and you learn when you see these beautiful pocket watches, you see how they developed the mechanism and how it is possible to make the mechanism by hand. That is not always the case today. Take, for example, a silicium hairspring. In 200 years, a simple watchmaker will not be able to replace a silicium hairspring. Good watchmakers from the past made movements so they would be able to be restored in the future. That is also important for me. In 100 years, a watchmaker will be able to repair and restore my watches."

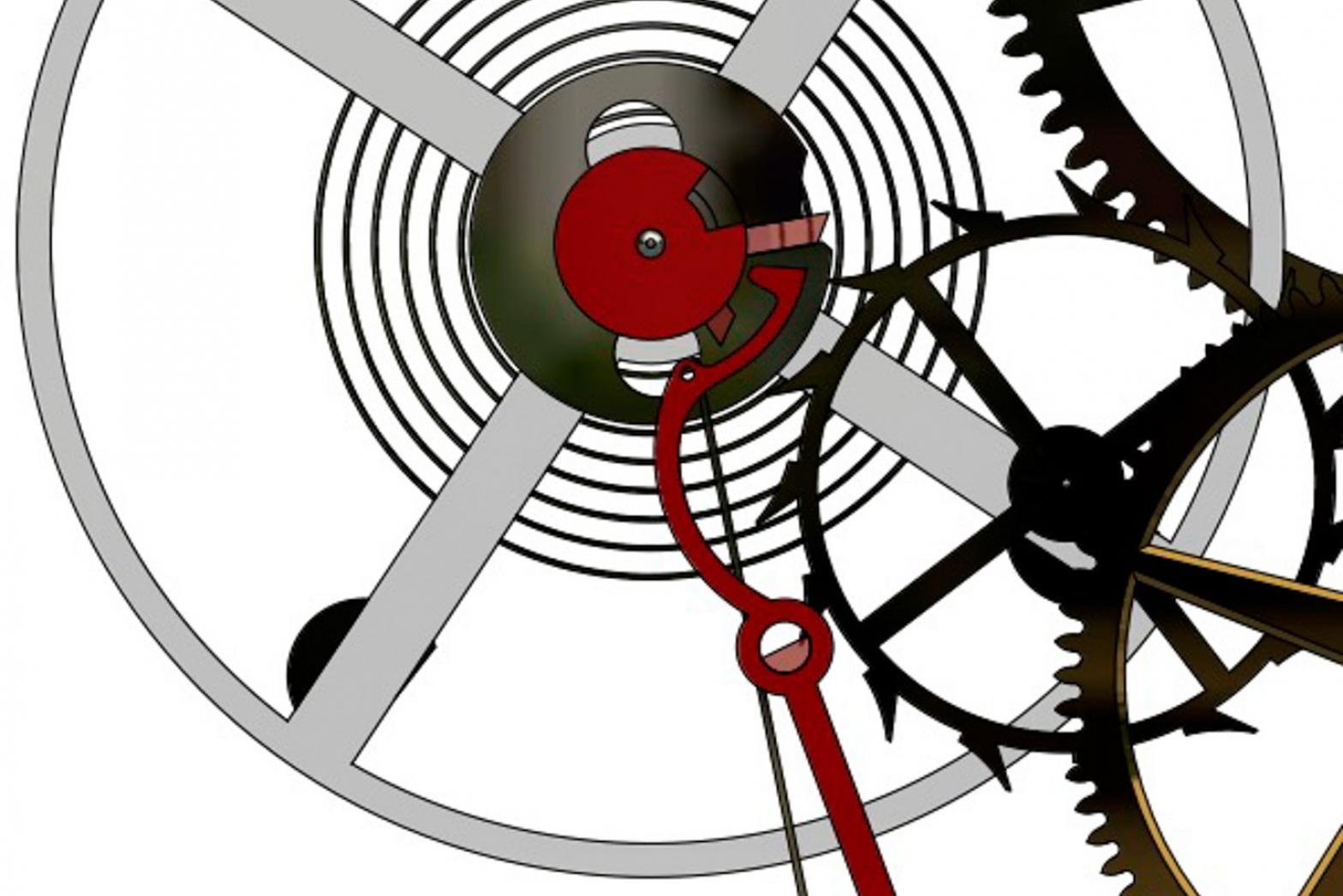

In addition to being future-proofed, the RP1 is traditional in some surprising ways. In fact, even if by some miracle of the time-space continuum, a watchmaker from 200 years ago found themselves servicing Pagès third creation, the mechanics — particularly the escapement — would be familiar. The most common escapement since the 19th century has been the Swiss Lever, an in-line mechanism which controls the rotation of the balance wheel with twin pallets mounted on a fork, with the rate controlled by the escape wheel. This near-ubiquitous mechanism is popular as the wheel and lever are not in constant contact, making for less wear and improved accuracy. On top of that, should the balance wheel stop, a slight movement is enough to start it again.

Raúl Pagès did not use a Swiss lever. He has created his own detent escapement, first developed in 1748 by Pierre Le Roy. Today, it is very much a rarity. The detent uses a single pallet attached to a thin spring blade with one impulse per cycle. This allows the balance wheel a wider rotation and less interference, resulting in much greater accuracy. Indeed detent escapements are as close as balance-wheel equipped watches come to meeting the accuracy of quartz technology. But there is a price to be paid for this precision. The most significant is a lack of shock resistance; the design of the detent means that a jolt or a bump could result in the pallet and balance locking. The other downside is that a detent escapement is less easy to start, needing, as Pagès describes, a 'kickstart'.

The RP1 elevates the traditional detent and makes it more suitable for daily wear in the modern world by adding an element of shock resistance, what Pagès calls an 'anti-tripping' mechanism, his pivoted detent mechanism, which sees a safety roller placed on the balance staff. It appears to be quite effective.

Pagès explains why he chose this uncommon escapement for his debut in-house caliber: "It's very specific, for watchmakers and geeks. To me the detent escapement is better than a swiss lever because you have a direct impulse of the escape wheel on the balance wheel. It's very efficient. You also have less friction than a Swiss lever escapement, and the isochronism is better for the accuracy of the balance wheel. But today it's a bit like a tourbillon. Right now, a very simple swiss lever escapement is more accurate than any tourbillon. The appeal is for the art of watchmaking, for the technical challenge and, of course, for beauty."

Of course, the peculiarities of this unique caliber aren't the only very specific choices that Pagès has made with the RP1; there's also the dial, specifically the colors. Regulator style watches, by and large, tend to hew pretty closely to a classical, scientific-instrument-type design language, which makes perfect sense given that this is exactly what they were initially intended for. The RP1, however, adds some flair into the mix with its open, minimal and modernist design that is surprisingly structural for something so simple. It also features a vibrant blue small seconds subdial. That blue, somewhere between duck egg blue and that of a summer sky, has not been chosen at random. It's a color that's inspired by one of Switzerland's most famous sons, the architect Le Corbusier, who was born in the watchmaking heartland of La Chaux-de-Fonds. It was a color the architect developed for his color collection, the Polychromie Architecturale. For Pagès, the link to Le Corbusier was a key part of the concept of the watch, a link to precision and pleasing Swiss design that is just as relevant as the connection to historic chronometric devices. However, this clarity of vision could be a risky decision for an emerging independent watchmaker, a space where customisation and the customer's involvement in the process is a normal part of business.

"People really like to have contact with the watchmaker who will make the watch for them, and to be involved in the process. You want to involve the end customer in the process and give them updates." Pagès explains. This flexibility only goes so far, though; "Lots of people ask me if it is possible to change the color of the dial and I refuse. "It's part of my creative process. The blue color is part of the concept of the watch. So I will refuse to change the dial, the proportions, the materials or the finishing. It's very important for me for all the watches to be similar. If someone wants a special engraving or name on the back, that's okay, as long as it doesn't affect the aesthetic of the watch."

This clear-minded approach doesn't seem to have affected the popularity of Pagès latest creation, as since the Régulateur à détente RP1 was announced, the reception has been incredibly successful both critically and commercially. "Right now I want to stop the orders for the RP1, I will have two to three years of work to deliver the pieces, and I want to take the time to develop other projects at the same time. It is important for me to make time to develop future projects and the commitment on the RP1 allows that sort of stability. It is an interesting time to be an independent watchmaker; more and more people are trusting the independents, but we have to be careful and not get too big."

The appeal of an independent watchmaker is strong; the image of a craftsperson who toils away in solitude, obsessively polishing baseplates and honing their skills is a powerful one. But, as Raúl Pagès illustrates, it is an incomplete picture. Of course, Pagès is an intellectual, massively skilled watchmaker forging his own path, but the direction of that path has been determined by not just his life in the cradle of watchmaking, his formative years in the workshops of Parmigiani and Patek Philippe, but by hundreds of year of horological history, history enshrined in objects that Pagès has learned to rebuild and repair. This upbringing has clearly formed Pagès philosophy and approach to watchmaking, which is simultaneously inspired by the past, but looks to the future.